3.1 (Informal) Set definition

The number of elements of a finite set is called it’s cardinality and is denoted .

3.2 Set Equality

.

3.1 Single element sets

For any sets and ,

Ordered Pairs

We can model ordered pairs (tuples) by defining

Set-Builder Notation

We can write a set in the following two ways:

- lists all for which the predicate is true

- lists the images of all by function for all .

Subsets

3.3 Subset

The set is a subset of the the set denoted if every element of is also an element of ,

3.2 Equality as double Subset

3.3 Transitivity of Subsets

3.4 Union and Intersection

The union of two sets and is defined as and their intersection is defined as

This can be extended to several sets, where and

3.5 Difference of two Sets

The difference of two sets and , denoted is the set of elements that are in without being in :

3.4 Laws of union and intersection

Idempotence: ; ;

Commutativity: ; ;

Associativity: ; ;

Absorption: ; ;

Distributivity: ; ;

Consistency: .

It is intuitive to think about operations on sets like logical operations:

- and

- and the other way around.

Empty set

3.6 Empty Set

A set is called empty if it contains no elements

3.5 Uniqueness of the Empty Set

There is only one empty set, which is often denoted or .

3.6 The empty set is a subset of every set

Constructing the Natural Numbers

We can construct the natural numbers using the following definitions from empty sets: , , , etc…

Natural number

The successor of any number is then .

Power Set

3.7 Power Set

The power set of a set , denoted is the set of all subsets of :

Cardinality of the Power set

For a finite set with cardinality , the power set has cardinality (hence the name power set and alternative notation ).

Cartesian Product of Sets

3.8 Cartesian Product

The Cartesian Product of two sets and is the set of all ordered pairs with the first component from and the second component from :

Cardinality of Cartesian product

The cardinaliity of

The Cartesian product is not associative and The first would give , the second .

Relations

3.9 Binary Relation

A (binary) relation from a set to a set (also called an (, )-relation) is a subset of . If , then is called a relation on .

Instead of one usually writes .

3.10 Identity relation

For any set , the identity relation on , denoted or simply id) is the relation .

Number of relations on a finite set

On a set of cardinality there are possible distinct relations. This is because .

We can represent any relation from finite sets as a boolean matrix . If then the corresponding matrix entry if set to .

We can also represent relations as a directed graph, the nodes of which correspond to the elements of and while the edges represent relations.

3.11 Inverse of a relation

The inverse of a relation is the relation defined by

In the matrix representation, the inverse corresponds to the transpose. In the graph representation, the inverse if reversing the direction of all edges.

The inverse of the inverse being equal to the element itself needs to be re-proven every time we want to use it (in the exam for example)!

Example On the set , the inverse of the relation is the relation .

3.12 Composition of Relations

Let be a relation from to and let be a relation from to . Then the composition of and , denoted (or also ) is the relation from to defined by:

The -fold composition of a relation on a set with itself is denoted .

Example If is the parenthood relation on the set of all humans, then is the grand-parenthood relation.

In the matrix representation, composition is matrix multiplication. In the graph representation, the composition corresponds to the natural composition of two graphs, there is a path from to if there is a path from to in graph and to in graph .

3.7 Associativity of composition

The composition of relations is associative, i.e., we have .

Note that this is important. This means that for example . See FS24 Task 1 c) for a good exercise.

3.8 Inverse of composition

Let be a relation from to and let be a relation from to . Then the inverse:

Properties of relations

Reflexivity

3.13 Reflexivity

A relation on a set is called reflexive if is true for all , i.e. if

3.14 Irreflexivity

A relation on a set is called irreflexive if is true for all , i.e. if

Example The relations on are reflexive, but are not.

Symmetry

3.15 Symmetry

A relation on a set is called symmetric if is true for all , i.e. if

Example The relation on is symmetric.

You can easily see that in matrix representation this corresponds to the transpose being equal to itself, i.e. the definition of a symmetric matrix.

3.16 Antisymmetry

A relation on a set is called antisymmetric if is true for all , i.e. if

Example The relations are antisymmetric. Example The relation on is antisymmetric as if but on it is not as the negative of an element divides it’s positive counterpart.

This is equal to the matrix not being symmetric. In the graph representation this means that there is not a single cycle of length 2, no edge from to and to .

Note that antisymmetric is not the negation of symmetry. A relation (for example the relation ) can be both at the same time.

Transitivity

3.17 Transitivity

A relation on a set is called transitive if is true for all .

Example The relations are all transitive on .

3.9 Transitivity of self-composition

A relation is transitive if and only if . This is intuitive if -ary self-composition is viewed as finding paths of length in the graph.

Transitive Closure

3.18 Transitive Closure

The transitive closure of a relation on a set , denoted is

You can view the transitive closure as the “reachability relation” which is only true for a pair if there is a path of finite length from to in relation .

Equivalence Relations

3.19 Equivalence Relation

An equivalence relation is a relation on a set that is reflexive, symmetric and transitive.

3.20 Equivalence Classes

For an equivalence relation on a set and for , the set of elements of that are equivalent to is called the equivalence class of and is denoted as :

Example The equivalence classes of are the sets , and .

There are two trivial equivalence classes: the complete relation , for which there is a single equivalence class and the identity relation for which the equivalence classes are all singletons .

3.10 Intersection of two Equivalence relations (on the same )

The intersection of two equivalence relations (on the same set) is an equivalence relation.

Example The intersection of .

Partitions

3.21 Partition of a set

A partition of a set is a set of mutually disjoint subsets of that cover , i.e. a set (for some index set ) satisfying

Partitions and equivalence classes capture the same relationship.

3.22 Quotient Set

The set of equivalence classes of an equivalence relation , denoted by is called the quotient set of by or simply modulo , or mod .

3.11 Equivalence classes form a partition

The set of equivalence classes of an equivalence relation on is a partition of .

Definition of the rational numbers

Consider the set and the equivalence relation defined as follows This relation is reflexive, symmetric and transitive. All pairs correspond to the same rational number and all equivalence classes correspond to distinct equivalence classes.

Partial Order Relations

The definition of a partial order is the same as that for an equivalence class, we simply replace the symmetry condition by an antisymmetry condition.

Partial order

A partial order (or simply an order relation) on a set is a relation that is reflexive, antisymmetric and transitive. A set together with a partial order on is called a partially ordered set (or simply poset) and is denoted as .

Example An example for a poset would be or . is not a partial order as it’s not reflexive. Example The subset relation on the power set of is a partial order: is a poset. Example The relation is both an equivalence relation and a partial order relation.

In the graph representation, a partial order has no cycles (transitive, but no symmetry).

Equal and strict

For any relation , is defined as .

3.24 Comparable and Incomparable

For a poset , two elements and are comparable if or ; otherwise they are called incomparable.

3.25 Totally and partially ordered

If any two elements of a poset are comparable, then is called totally ordered (all elements can be compared) (or linearly ordered) by .

Example is a totally ordered poset. So is any subset of for the relation . Example The poset is not totally ordered if (see nor ). Example The poset is not totally ordered ().

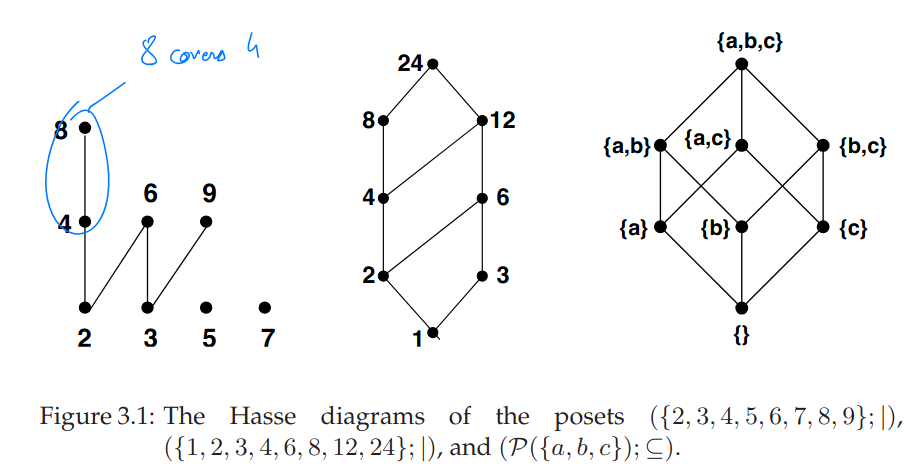

Hasse Diagrams

3.26 Covering

In a poset an element is said to cover an element if and there exists not with and (i.e. between and ).

Example In a hierarchy covering means that is the direct superior of .

3.27 Hasse Diagram

The Hasse Diagram of a (finite) poset is the directed graph whose vertices are labeled with the elements of and where there is an edge from to if and only if covers .

Posets and Lexicographic Order

3.28 Direct Product

The direct product of posets and , denoted , is the set with the relation (on ) defined by

3.12 Direct Product of Posets is a Poset

is a poset.

Lexicographic order

For given posets and , the relation defined on by is a partial order relation.

This is useful as if both the first and second posets are totally ordered, then so is the lexicographic order on .

Example This is how a phone book or a dictionary would be ordered.

Special Elements in Posets

Special Elements of Posets

Definition 3.29. Let be a poset, and let be some subset of . Then

- is a minimal (maximal) element of if there exists no with .

- is the least (greatest) element of if for all .

- is a lower (upper) bound of if for all .

- is the greatest lower bound (least upper bound) of if is the greatest (least) element of the set of all lower (upper) bounds of

The greatest lower bound and least upper bound are sometimes denoted and .

Example The poset has no least or greatest elements (as not all are comparable). are minimal elements. are maximal elements. The number is the lower bound (even the greatest lower bound) of the subset . has no lower (nor upper) bound.

3.30 Well-Ordering

A poset is well-ordered if it is totally ordered and if every non-empty subset of A has a least element.

Every totally ordered finite poset is well-ordered. The property of well ordering is of interest only for infinite posets. is well ordered by . Any subset of a well-ordered set is well-ordered (by the same relation).

Meet, Join and Lattices

3.31 Meet and Join

Let be a poset. If and (i.e. the set of ) have a greatest lower bound, then it is called the meet of and , often denoted . If and have a least upper bound, then it is called the join of and , often denoted .

3.32 Lattices

A poset in which every pair of elements has a meet and join is called a lattice.

Example The posets , and are lattices. Example The poset is a lattice. The meet of two elements is their gcd, while their join is the lcm. .

Functions

Functions are a special type of relation.

3.33 Functions

A function from a domain to a codomain is a relation from to with the special properties (using the relation notation ):

- ( is totally defined)

- ( is well defined)

3.34 Set of all functions

The set of all functions is denoted as .

3.35 Partial functions

A partial function is a relation from to such that only condition 2. of def 3.33 holds (, is well defined).

Two partial functions are equal if they are equal as relations (they agree for all arguments).

3.36 Image

For a function and a subset of , the image of under , denoted , is the set

3.37 Image or Range

The subset of is called the image (or range) or and is also denoted .

Example The function defined by has as it’s range the set .

3.38 Preimage

For a subset of , the preimage of , denoted is the set of values in that map into :

Example The preimage of the interval is .

3.39 Injectivity, Surjectivity and Bijectivity

A function is called 1 ) injective (or one-to-one or an injection) if for we have , i.e. no two distinct values are mapped to the same function value (there are no “collisions”). 2) surjective (or onto) if , i.e. for every for some (every value in the codomain is taken on for some argument). 3) bijective (or a bijection) if it is both injective and surjective.

Proving Injectivity and Surjectivity:

- Injectivity:

- Assume that and show that if which is a contradiction

- Surjectivity:

- show that we can find an a such that

- , let , but there is no thus not surjective.

3.40 Inverse of a bijection

For a bijective function , the inverse (as a relation) is called the inverse function of , usually noted as .

3.41 Composition

The composition of a function and a function denoted by or simply is defined by

Composition of functions and properties

- The composition of two injective functions is an injective function

- The composition of two surjective functions is a surjective function

- The composition of two bijective functions is a bijective function

Function Composition Order

- Order of application: In , function is applied FIRST, then

Read right to left: means “first do , then do ”

= apply to first, getting , then apply to result

- Different from relation composition:

- Relations: where and (same order)

- Functions: where and (reversed notation)

Memory Aid: In , the order of letters (left to right) is OPPOSITE to order of application (right to left).

3.14 Associativity of function composition

Function composition is associative, i.e. .

Countable and Uncountable Sets

3.42 Equinumerous, dominates, countable and uncountable

(i) Two sets and are equinumerous, denoted , if there exists a bijection . (ii) The set dominates the set , denoted if for some subset or, equivalently, if there exists an injection . (iii) A set is countable if and uncountable otherwise.

Example The set is countable and by the bijection .

Strict Smaller Cardinality

We say that has a strictly smaller cardinality than if . There’s an injection but no bijection from to .

3.15 Relations and Countability

(i) The relation is an equivalence relation. (ii) The relation is transitive: . (iii) .

Countable

is countable if or for an , i.e. .

3.16 Definition of

is the Cantor-Bernstein-Schroeder Theorem.

Between finite and countably infinite

For any finite sets and , we have if and only if . A finite set never has the cardinality as one of it’s proper subsets.

This is not true for infinite sets however, as the set of odd numbers as there exists a bijection between both sets, .

3.17 Countable Sets

A set is countable if and only if it is finite or if .

This means that there is no cardinality level between finite and countably infinite.

Well-Ordering Principle of .

Every set of natural numbers has a least element. This fact is called the well-ordering principle of .

Important Countable Sets

3.18 Finite binary sequences

The set of finite binary sequences is countable.

3.19 Product of is countable

The set of ordered pairs of natural numbers is countable.

3.20 Cartesian product of any countable sets is countable

The Cartesian product of two countable sets and is countable, i.e. .

3.21 is countable

The rational numbers are countable.

3.22 Countable sets

Let and for be countable sets. (i) For any , the set of -tuples over is countable. (ii) The union of a countable list of countable sets is countable. (iii) The set of finite sequences of elements from is countable.

Uncountability of .

3.43 Definition of

Let denote the set of semi-infinite binary sequences or, equivalently, the set of functions .

*Note that the difference between and is that all elements in the first have infinite length, while the second considers elements of all lengths.

3.23 Uncountability of

The set is uncountable.

This can be proven by Cantor’s diagonalisation argument. We can write instead of .

We also can show that is uncountable und thus is too.

To prove the uncountability of a set , we use the following proof schema: 2. By Injection - Show an injection from () and that is uncountable, ex: . - You can use any known uncountable sets: - If was countable (), then by the transitivity of this would imply that which is a contradiction as is known uncountable. 3. By Diagonalisation - Assume uncountability and show a contradiction (ex: Diagonalisation)

4-Schritt Muster für Uncountability:

- Injektion finden: Konstruiere , sodass

- Funktion verifizieren: Zeige dass well-defined und total ist, und für alle .

- Injektivität beweisen: Zeige oder direkt .

- Schluss: . Annahme führt zu Widerspruch via Transitivität. Deswegen ist uncountable: .

Tricks: Complement Trick:

- Find uncountable such that .

- Show that countable which proves that uncountable.

- You have to prove this implication in the exam:

- Assume is countable towards contradiction.

- Show that is countable as well under this assumption.

- Thus also countable (Theorem 3.22: Union of countable is countable).

- But which is uncountable - contradiction!

- Verwende oder statt falls einfacher.

Uncomputable functions

3.44 Computable functions

A function is called computable if there is a program that, for every , when given as input, outputs .

3.24 Uncomputable functions

There are uncomputable functions .

This can be proven by thinking about computer programs as bitstrings. As the set of finite bitstrings is countable, while the set of functions is not, there must be uncomputable functions.

The Halting problem is a prominent example of an uncomputable function. It is undecidable.

Bemerkung der Lecture am 27.10.2025

Wir haben . In fact the power set of any set dominates that set.

We also have the Kontinuumshypothese which states that there is no such that .