This chapter deals with some basics regarding number theory. It in particular focuses on the natural/whole numbers, but the concepts can be applied to any Field.

Prerequisites

We assume that the concepts of , addition, multiplication, negation, associativity, commutativity, distributivity, and are clear.

4.2 Divisors and Division

4.1 Divides

We say that divides for any integers (denoted ) if . is a divisor (de: Teiler) of , a multiple (de: Vielfaches) of and the quotient (de: Quotient).

Every non-zero integer is a divisor of . Moreover and are divisors of every integer.

We define a prime as .

4.1 Euclidean Division

For all integers and there exist unique integers and satisfying

is called the remainder (de: Rest).

4.2 Greatest Common Divisor

For integers and (not both ), an integer is called a greatest common divisor of and if divides both and and if every common divisor of and divides , i.e. if

4.3 GCD

For (not both 0), one denotes the unique postive greatest common divisor by and usually calls it the greatest common divisor. If , then and are called relatively prime.

Proof if and are coprime.

This is an important result for the exam: Which is the same as saying such that . Since and , we have: Since , by Bézout’s identity: Now we can write: \begin{align} a &= 1 \cdot a \\ &= a \cdot (pu + qv) \\ &= pua + qva \\ &= pu \cdot qk' + qv \cdot pk \\ &= pq(uk' + vk') \end{align} Thus .

4.2 GCD relations

For any integers and we have

This implies the necessary step for Euclid’s algorithm

4.4 Ideals

For , the ideal generated by and , denoted , is the set Similarly, for a single integer we have

4.3 All ideals can be generated by a single integer

For there exists such that . This implies that every ideal can be generated by a single integer.

4.4 GCD

Let (not both 0). If , then is a greatest common divisor of and .

4.5 GCD result of ideal

For (not both ), the exist such that

This is Bézout’s identity.

There is an algorithm (Euclidean algorithm) which can be used to find the values of and for this decomposition. It works by computing the euclidean decomposition and replacing by in , rince and repeat until you arrive at . Then you can use back propagation to find the values for the equation . Knowing this algorithm is necessary for the exam!

Walk-through:

- Gleichungen der Reste:

- Rückwärtssubstitution:

- Ergebnis: und

4.5 Least common multiple

The least common multiple of two positive integers and , denoted , is the common multiple of and which divides every common multiple of and , i.e.

4.3 Primes

4.6 Primes

A positive integer is called prime if the only positive divisors of are and itself. An integer greater than that is not prime is called composite.

4.6 Fundamental theorem of arithmetic

Every positive integer can be written uniquely (up to the order in which factors are listed) as the product of primes.

We need to state this theorem when decomposing any integer into it’s prime factors!

4.7 Prime divides one in product

If is a prime which divides he product of some integers , then divides one of them, i.e. for some

We can now express the and in this form. Let and be

Then and

We can also see that as .

4.9 Infinity of primes

There are infinitely many primes.

4.10 Prime density

Gaps between primes can be arbitrarily large, i.e. for every , there exists such that the set contains no prime.

4.7 Prime counting function

The prime counting function is defined as follows: For any real is the number of primes .

4.11 Prime counting function limit

To test whether a number is prime, we have to test every smaller integer which could be a divisor, there is one shortcut however.

4.12 Prime divisors

Every composite integer has a prime divisor .

Congruences and Modulo Arithmetic

4.8 Congruence

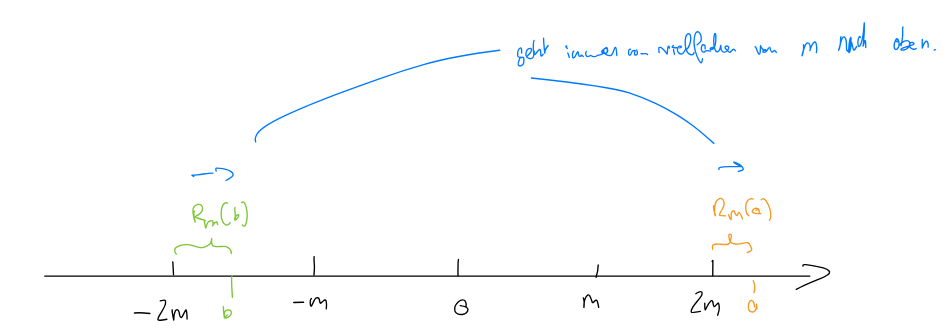

For with , we say that is congruent to modulo if divides . We write or simply , i.e.,

We define the function as the smallest positive for which .

4.13 Modulo Equivalence Relation

For any , is an equivalence relation on .

4.14 Modular arithmetic

If and then

Simplifying calculations

4.15 Modular reduction of a multivariate polynomial

Let be a multi-variate polynomial in variables with integer coefficients, and let . If for , then

We are often interested in only the remainder of an integer calculation. We want the result to be bounded below the we are moduloing against. We can use the fact that is an equivalence relation and since there are equivalence classes namely . Each class has a smallest, natural representative in the set .

4.16

For any with ,

Together these two properties imply that:

4.17 Polynomial reduction

Let be a multi-variate polynomial in variables with integer coefficients, and let . Then

Example This is what helps us reduce things like .

Diophantine Equations

We can show that certain equations don’t have solutions in using modular arithmetic. We will show this on the example: - is always even (show this using case distinction from )

- is always odd (again by case distinction).

Try using and at first, as this will usually work.

Multiplicative inverses

4.18 Modular Inverse

The congruence equation has a solution if and only if . The solution is unique.

Note that this only works for as otherwise the rest would always be something and never 1.

4.9 Multiplicative inverse

If , the unique solution to the congruence equation is called the multiplicative inverse of a modulo . One also uses the notation or .

Chinese Remainder Theorem

4.19 The Chinese Remainder Theorem

Let be pairwise relatively prime integers and let . For every list with for , the system of congruence equations \begin{align} x &\equiv_{m_1} a_1 \\ x &\equiv_{m_2} a_2 \\ &\vdots \\ x &\equiv_{m_r} a_r \end{align} for has a unique solution satisfying .

Warum funktioniert die CRT-Konstruktion? Die Summe: Betrachte für ein festes :

- Für : ist durch teilbar, also . Somit .

- Für : , also . Ergebnis: , nur der -te bleibt als . Also erfüllt jede Kongruenz!

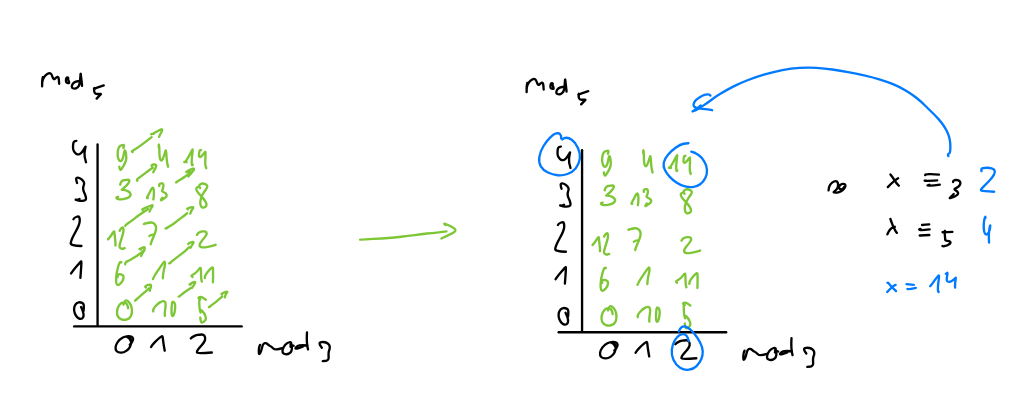

We can also see the CRT as saying that for all pairwise relatively prime, there exists a unique solution mod for the equations.

Or seen still otherwise, there is a unique bijective mapping from the numbers to each modulo . This mapping can be made visible in such a table:

Technique

The Chinese Remainder Theorem is very useful to make big operations inside an easier to process.

Example: Computing

can be decomposed into two sub-remainders. As , we can use: and Thus and . Then we have and , thus .

General Technique When the final remainders are not both simple values like 1 and 1, you need to find such that:

- where .

Solution: Use the formula where (for the specific case of a decomposition into two formulas).

Brief Example: If and , then:

- Find (since )

- Find (since )

- Calculate:

- Therefore

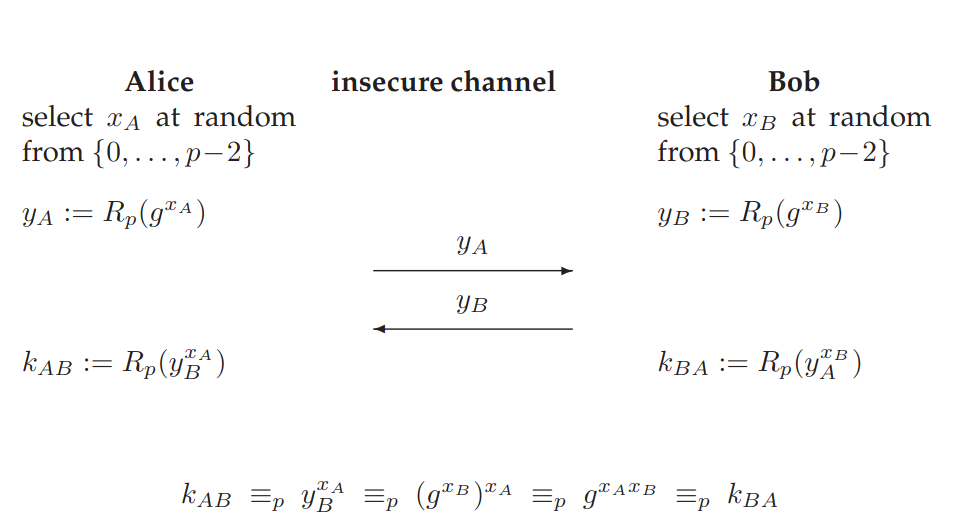

Diffie-Hellman Key-Exchange

The Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol is used to establish a shared key over an insecure channel.

Because modular exponentiation is hard to invert (we basically need to try all possible numbers), we can safely share the and know that an attacker would never be able to figure out the from that.

Example Calculation: We use and , which are public.

- In private Alice and Bob each select a random element from that is not (i.e. the inverse).

- Alice , Bob

- Then

- Then

- The secret key is then . Thus both are left with the same key. The attacker Eve would have to solve the Discrete Logarithm problem to recover each participants choice of key.

Exercises

Reducing expressions like

As , we can reduce the exponent modulo (see Lagrange’s theorem in chapter 5). Thus .

For this to work however, we need the number and the order of the group (modulo remainder) to be coprime, i.e. .