Algebra

5.1 Arity of a function

An operation on a set is a function , where is called the arity of the operation.

We have unary and binary operations. A nullary operation is called a constant.

5.2 Algebra

An algebra (or algebraic structure or -algebra) is a pair where is the set (the carrier of the algebra) and is a list of operations on .

Example denotes the integers with the two binary operations and and the unary operation (taking the negative) and two constants and , the neutral elements of addition and multiplication.

You can draw a sort of table that represents the function on an algebra:

| * | a | b | c |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | a |

| b | c | a | b |

| c | a | b | c |

| From this we can read of certain properties. |

Monoids

An algebra can have special properties, for example: (1) a neutral element, (2) associativity and (3) inverse elements. Commutativity is not as interesting.

5.3 Neutral Elements

A left [right] neutral element (or identity relation) of an algebra is an element such that ( ) for all . If for all , then is simply called neutral element.

If the operation is addition, then is usually denoted , if the operation is multiplication then the operation is denoted .

5.1 Uniqueness of neutral element

If has both a left and a right neutral element, then they are equal. In particular can have at most one neutral element.

Commutativity and unique neutral element

The uniqueness of the neutral element does not imply that the group is abelian.

Think of the identity matrix for the group of matrices and element-wise multiplication. even though multiplication is not commutative.

Example The empty sequence is the neutral element of the group of sequences over the alphabet with concatenation.

5.4 Associativity

A binary operation on a set is associative if for all .

Associativity is very important! It means that is uniquely defined and independent of the order of “execution”:

Example Not all operations are associative, exponentiation on the integers is not for example.

5.5 Monoids

A monoid is an algebra where is associative and is the neutral element.

Example , are examples of monoids.

Groups

5.6 Inverses

A left [right] inverse element of an element in an algebra with neutral element is an element such that (). If , then is simply called an inverse of .

5.2 Uniqueness of the inverse

In a monoid , if has a left and right inverse, then they are equal. In particular, has at most one inverse.

Example A function has a left inverse if is injective, it has a right inverse if surjective. Hence has an inverse if and only if is bijective.

5.7 Group

A group is an algebra satisfying the following axioms:

- G1 is associative

- G2 is a neutral element: for all .

- G3 Every has an inverse element , i.e. .

*We can write instead of the longer version. The inverse in a group with addition is denoted and the inverse in a group with multiplication is .

If we refer back to the tables representing the results of the operation, we can see that there never can be two elements leading to the same element under the operation. Thus every row and column has to contain every element once (inverse needs to exist).

Proving something is a group

We need to prove G1, G2, G3. We only need to prove closure if it’s not obvious that the operation’s range for example is identical to the group’s carrier.

5.8 Abelian or Commutative Groups

A group (or monoid) is called commutative or abelian if for all .

5.3 Group properties

For a group we have for all :

- (i) .

- (ii) .

- (iii) Left cancellation law: .

- (iv) Right cancellation law: .

- (v) The equation has a unique solution for any and . So does the equation .

Useful properties of groups

- (as you can cancel out the by the cancellation laws)

- (same…)

We want the axioms of a theory to be minimal. We can show that . We only need to have for G2, which we call axiom G2’. The equation is then implied by all axioms. The same can be done for G3, thus creating G3’.

Examples The set is the set of permutations of elements (the set of bijections ). A bijection has an inverse . It follows from the associativity of function composition that the composition of these permutations is also associative. We thus have the symmetric group on elements. is non-abelian for .

Reflections and symmetries of geometric figures are another important sources of groups (ex: 8 symmetries on the cube).

Direct Products

5.9 Direct Product

The direct product of groups is the algebra where the operation is component-wise:

Example The group . The carrier is with the neutral element . It follows from the CRT that is isomorphic to .

Direct product Isomorphisms

if and only if .

Examples 5.16: as they have the same prime factorisation. You can “redistribute” factors. The isomorphism where is given by the CRT for and .

Cyclicity of Direct Product

is cyclic if and only if both are cyclic and .

Example is not cyclic, as it has no element of order .

Homomorphisms

5.10 Group Homomorphism

For two groups and , a function is called a group homomorphism if, for all and ,

If is a bijection from to , then it is called an isomorphism, and we say that and are isomorphic and write .

What this means is that it does not matter if we first apply the function and then perform the operation or if we perform the operation and then map the result. The same arguments produce the same output in both groups.

Does Every Homomorphism have to be injective? No, we could map all elements to the neutral element, which would still satisfy the property.

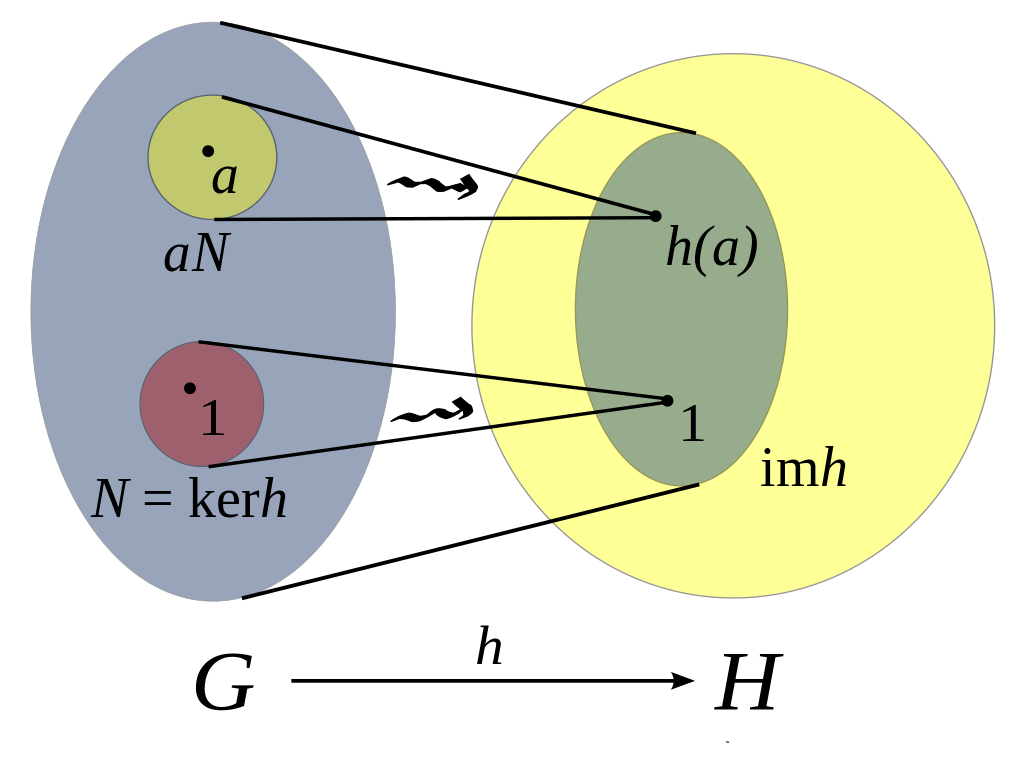

This picture clarifies the properties of homomorphisms:

- is a homomorphism here.

- is the kernal of the map , which is basically the nullspace (set of all elements mapped to the neutral).

- is the image, the set of all elements mapped to .

- is the coset where , thus .

Isomorphisms: An isomorphism is simply a homomorphism which is also bijective. This means that the structure is preserved both ways, i.e. the groups behave the same. Think of two jigsaw puzzles that look completely different, but the same piece goes into the same place on both (same cutout was used).

Prove an Isomorphism:

- Define a Candidate Map: Identify a function that you suspect to be an isomorphism.

- Verify the Map is Well-Defined: Ensure that the proposed map is unambiguous and consistent. That is, for any , is uniquely determined.

- Verify the Map is Totally Defined: Confirm that the map is defined for all elements of (i.e., applies to every element of ).

- Verify the Map Maps to the Codomain: Ensure that for all so that the image of lies entirely within .

- Check the Homomorphism Property: Verify that for all . This ensures the map preserves the group operation.

- Check Injectivity: Prove that is one-to-one by showing that if , then .

- Check Surjectivity: Prove that is onto by demonstrating that for every , there exists such that .

- Conclude Isomorphism: If the map satisfies the homomorphism property, is well-defined, maps to the codomain, and is bijective, then is an isomorphism, and .

5.5 Group Homomorphism properties

A group homomorphism from to satisfies (not iff. but only ):

- (i)

- (ii) for all .

Example The logarithm function is a group homomorphism from to since . (It’s also an isomorphism) Example The projection of points in down to is a homomorphism but not an isomorphism as it’s not a bijection.

Subgroups

5.11 Subgroups

A subset of a group is called a subgroup of if is a group, i.e., if is closed with respect to all operations:

- (1) for all

- (2)

- (3) for all

Trivial subgroups

For any group there exist two trivial subgroups:

- the set

- itself.

Example The group has the following subgroups , , , , .

Order of a Group Element and Group

Notation

We use the following notation to talk about order:

- for

- for

The following laws therefore also hold:

5.12 Order of an element

Let be a group and let be an element of . The order of , denoted , is the least such that , if such an exists:

is said to be infinite otherwise, written .

Some useful facts

- By definition, .

- If for some , then , i.e. is it’s own self-inverse.

- If , we say has “volle Ordnung” (such an element must not always exist).

Example The order of in is . This can be easily seen since , i.e. we need to add to itself times to reach which is a multiple of , i.e. .

Example The order of any integer in is as we never loop around (carrier is an infinite group)…

5.6 Finite Order in Finite Groups

In a finite group , every element has a finite order.

See proof in script.

5.13 Order of a Group

For a finite group , is called the order of . (same name as the order of an element).

Cyclic Groups

Power modulo order

In a group of finite order, for as .

5.14 Generators

For a group and , the group generated by , denoted , is defined as

This is a group, the smallest subgroup of a group containing the element .

For finite groups we have .

Generators of

We know that is generated by all for which .

Proof: Assume . This And then using Bézout:

5.15 Cyclic group and generator

A group generated by an element is called cyclic and is called a generator of .

- Associativity inherited from

- Neutral element is always in as .

- The inverse is by definition.

A group can have more than one generator. In particular, if is a generator, then is also a generator.

Example and

5.7 Isomorphism from cyclic groups to additive groups

A cyclic group of order is isomorphic to (and hence abelian).

Standard notation for cyclic groups

We use as our standard notation for cyclic groups of order .

The group denoted by is always meant in conjuction with the operation modulo .

This group also only contains the positive numbers up to as the negatives are equal a positive number .

Generators of

The group is cyclic for every , where is a generator. The generators of are all , coprime to , i.e. for which .

Commutativity of

The group is abelian.

Order of Subgroups

5.8 Lagrange's Theorem

Let be a finite group and let be a subgroup of . Then the order of divides the order of , i.e., divides .

5.9 The order of every element divides the group order

For a finite group , the order of every element divides the group order, i.e., divides for every .

Proof We have a subgroup of of order , which according to Theorem 5.8 must divide .

Order of a generated group

We have the order .

5.10 Element to the power of the order is neutral

Let be a finite group. Then for every .

Proof for some by Corollary 5.9. Thus .

5.11 Prime order cyclic groups

Every group of prime order is cyclic, and in such a group every element except the neutral element is a generator.

Proof Only and for prime, thus only a generator for an , with or can divide . In the first case, and in the latter case .

Euler’s Totient function

5.16 Multiplicative Group over

(group with ) is not a group with respect to multiplication modulo , as elements that are not coprime to don’t have an inverse. Thus we need to remove all of these elements and have a group with .

5.17 Euler's Totient function

The Euler function is defined as the cardinality of :

5.12 Euler function from prime factorisation

If the prime factorisation of is , then

This comes from the fact that for prime and we have since exactly every th integer in contains a factor and thus elements don’t contain a factor , i.e. are in . Since the ‘s are pairwise relatively prime (obviously) by the CRT we have that . This holds as the CRT allows us to establish a bijection between each and a unique tuple where .

Number of divisors of

We can use a similar function to count the number of divisors of a number . Write . Then

5.13 Multiplicative group

is a group.

Proof Idea: This holds as for , and , thus . Thus this group is closed.

5.14 Fermat's Little Theorem

For all and all with , In particular, for every prime and every not divisible by ,

Proof Idea This follows from Corollary 5.10 that and the order of is is for prime.

5.15 Condition for a group to be Cyclic

The group is cyclic if and only if , , or where is an odd prime and .

RSA

-th Roots in a Group

5.16 Roots in a group

Let be some finite group (multiplicatively written) and let be relatively prime to . The function is a bijection and the (unique) -th root of , namely satisfying is where is the multiplicative inverse of modulo , i.e.

Proof Idea We have for some (as ). Thus for any we have as in the group .

The important reason why RSA works is that if is known, then can be computed from by using the extended euclidean algorithm. If we don’t know the order of the group we have to try all possibilities.

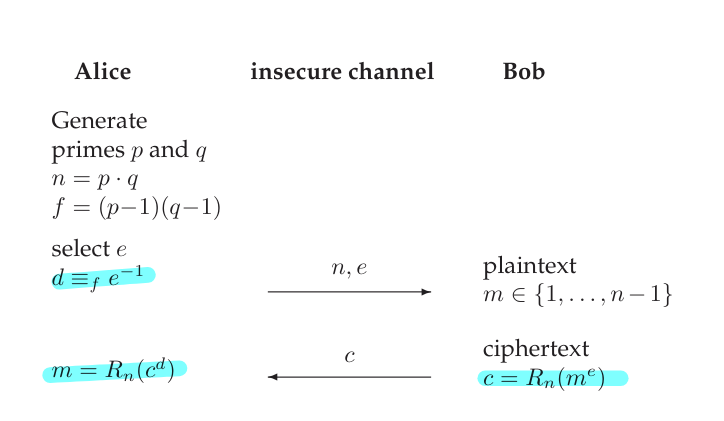

Description of RSA

Let and be two sufficiently large secret primes, where the product. The order of can be computed only if the prime factors are known. Otherwise, we have to try all possibilities, i.e. all elements in the group.

Public Encryption works like this: and the secret decryption is defined as where can be computed according to . (we have to choose an which is coprime to as otherwise it has no multiplicative inverse).

5.5 Rings and Fields

We now consider algebraic systems with two binary operations, usually called addition and multiplication.

Ring

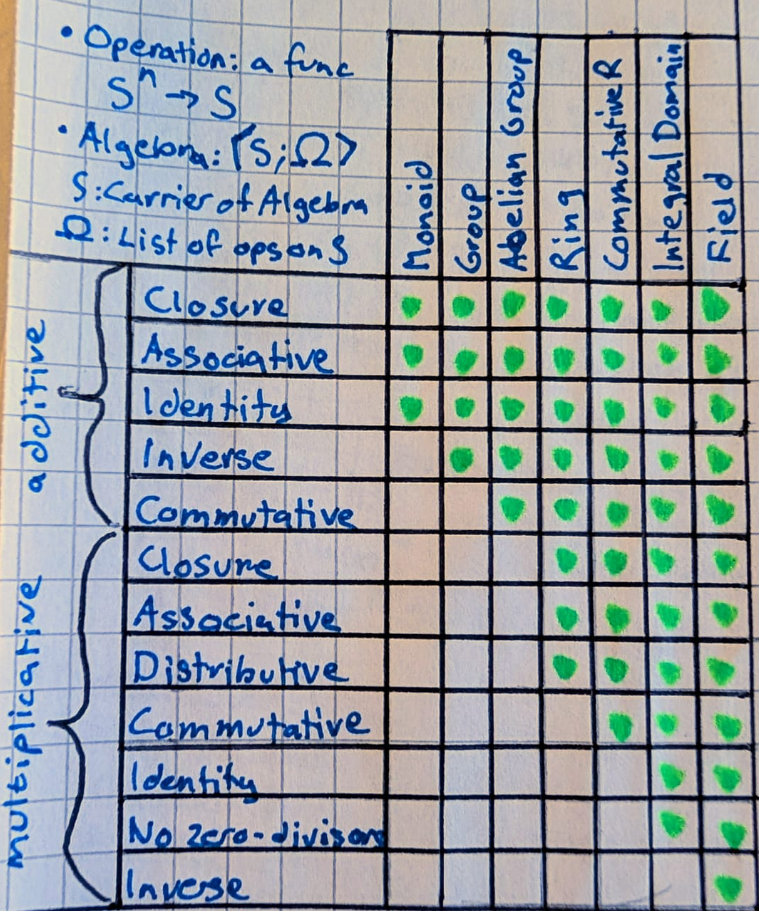

5.18 Ring definition

A ring is an algebra for which:

- is a commutative group.

- is a monoid.

- and for all (left and right distributive laws). A ring is called commutative if multiplication is commutative ().

Example and are (commutative) rings.

5.17 Ring Properties

For any ring , and for all :

- If is non-trivial (if it has more than one element), then .

0 has no multiplicative inverse, as is not possible according to (1). Therefore, requesting to be a group would make no sense.

5.19 Characteristic of a ring

The characteristic of a ring is the order of in the additive group if it is finite, and otherwise it’s (not !).

Example The characteristic of is as we can easily see.

Units and Multiplicative Groups

We can now impose some addition constraints onto the elements to get more interesting properties.

5.20 Units

An element of a ring is called a unit if is invertible, i.e. for some . (We write .) The set of units of is denoted by .

Example The units of are and . Therefore . In contrast, , as we can divide any two numbers.

5.1 Multiplicative group

For a ring , is a group (the multiplicative group of units of ).

This holds as we can easily see that every element of has an inverse by definition. Thus the axiom holds.

Divisors

Now, is a commutative ring.

5.21 Division

For (commutative), we say that divides , denoted if there exists a such that . In this case is called a divisor of and is a multiple of .

Every non-zero element is a divisor of . Moreover, and it’s inverse are divisors of every element.

5.19 Division properties

In any commutative ring:

- If and then , i.e. the relation is transitive.

- If then for all .

- If and , then .

We can then generalise the to any commutative ring.

5.22 GCD

For any ring elements and in (not both ), a ring element is called a greatest common divisor of and if divides both and if every common divisor of and divides , i.e. if

Zerodivisors and Integral Domains

5.23 Zerodivisor

An element of a commutative ring is called a zerodivisor if for some in .

5.24 Integral Domain

An integral domain is a (nontrivial, ) commutative ring without zerodivisors: For all we have .

Examples are integral domains. is not an integral domain if is not a prime, as every element not relatively prime to is a zerodivisor.

5.20 Integral Domain divison

In an integral domain, if then with is unique (and is denoted by or and called quotient).

Polynomial Rings

5.25 Polynomial Rings

A polynomial over a commutative ring in the indeterminate is a formal expression of the form for some non-negative integer , with .

The degree of , denoted , is the greatest for which .

The special polynomial (i.e., all the are ) is defined to have degree “minus infinity”.

Let denote the set of polynomials (in ) over .

The degree of the special polynomial , for which all coefficients are is .

A polynomial can also be understood as a simple list of coefficients, which doesn’t correspond to a function.

Degree of sum and multiplication

The degree of the:

- sum of two polynomials is at most the maximum of their degrees, i.e. it can only be equal or smaller.

- product of two polynomials is at most the sum of their degrees. It’s equal if is an integral domain (as otherwise for the highest coefficient).

5.21 Commutative Ring Polynomials

For any commutative ring , is a commutative ring.

5.22 Polynomials over integral domains

Let be an integral domain. Then

- is an integral domain.

- The degree of the product is the sum of their degrees.

- The units of are the constant polynomials that are units of : .

Fields

5.26 Fields

A field is a nontrivial commutative ring in which every nonzero element is a unit, i.e. .

Fields

In other words, a ring is a field if and only if is an abelian group.

Examples are fields, while and (for any ring ) are not fields.

5.23 field

is a field if and only if is prime.

Galois Fields

We denote the field with (thus has to be prime) elements by rather than .

Note that is a field, not a group! It’s not only isomorphic to but also to any polynomial fields of the same order.

In a field you cannot only add, subtract and multiply but also divide by any nonzero element. This is because in a field, the multiplicative monoid is also a group (without ).

5.24 Field Integral domain

A field is an integral domain.

5.6 Polynomials over a Field

5.6.1 Factorisation and Irreducible Polynomials

In the integers, we have the dual divisors and . In a field, this corresponds to all constant multiples of a polynomial dividing another.

Division in Fields

If divides , then so does for any nonzero . This holds because if , then .

5.27 Monic Polynomials

A polynomial is called monic if the leading coefficient is .

5.28 Irreducibility

A polynomial with degree at least is called irreducible if it is divisible only by constant polynomials (of ) and by constant multiples of (itself).

This has a couple implications:

- Every polynomial of degree is irreducible.

- A polynomial of degree is either irreducible or the product of two polynomials of degree .

- A polynomial of degree is either irreducible, or it has at least a factor of degree .

- A polynomial of degree is either irreducible, or it has a factor of degree or has an irreducible factor of degree .

Irreducibility check

We can check if a polynomial of degree is irreducible, by checking all monic irreducible polynomials of degree as possible divisors.

GCD in a polynomial field

The monic polynomial of largest degree such that and is called the greatest common divisor of and denoted .

Because a field is an Integral Domain, is also an integral domain. Therefore, we can also divide any two polynomials: (for ).

Division property

Because the ring has strong similarities to the integers there is also the division property here.

The analogy to in a polynomial ring is the degree, which measures the “size” of the remainder.

5.25 Division

Let be a field. For any and in there exists a unique (the quotient) and a unique (the remainder) such that

We denote as in the polynomial version.

Analogies between and , Euclidean Domains *

5.32 Euclidean Domain

A euclidean domain is an integral domain together with a degree function such that:

- For every and in there exist and such that and or

- For all nonzero and in , .

is such a euclidean domain which justifies theorem 5.25.

5.27 Fundamental theorem of arithmetic generalised

In a Euclidean domain every element can be factored uniquely (up to taking associates) into irreducible elements.

5.7 Polynomials as functions

We can interpret a polynomial in a ring as a function that evaluates the polynomial at at .

5.28 Polynomial evaluation

Polynomial evaluation is compatible with the ring operations:

- If then for any

- f then for any

Roots

5.33 Roots

Let . An element for which is called a root of .

5.29

For a field , is a root of if and only if divides .

This means that an irreducible polynomial of degree has no roots.

5.30 Irreducibility and roots

A polynomial of degree or over a field is irreducible if and only if it has no root.

This doesn’t work for polynomials of higher degrees as for example a polynomial of degree might be composed of irreducible polynomials of degree .

5.31 Number of Roots

For a field , a nonzero polynomial of degree has at most roots.

5.7.3 Polynomial Interpolation

A polynomial over of degree can be interpolated from any values. The same is true for any field.

5.32 Determine a polynomial

A polynomial of degree at most is uniquely determined by any values of , i.e. by for any distinct .

Interpolate a polynomial from values

Let for . Then is given by Lagrange’s Interpolation formula: where the polynomial is given by

Note that for to be well-defined, all constant terms in the denominator must be invertible. This is guaranteed in a field since for (as they are all distinct).

This is unique since if there was another then would have at most degree and thus at most roots. But since has the same roots, it’s .

5.8 Finite Fields

The Ring

In the same ways as there is and , there is also and .

Modulo in the Field

5.33 Congruence

Congruence modulo is an equivalence relation on , and each equivalence class has a unique representation of degree less than .

Example In we have

5.34 Definition of

Let be a polynomial of degree over . Then

5.34 Cardinality of finite field

Let be a finite field with elements and let be a polynomial of degree over . Then . This is the amount of combinations we have for coefficients and possible elements.

5.35 Ring properties of

is a ring with respect to addition and multiplication modulo .

5.36 Inverses

The congruence equation for a given has a solution if and only if . The solution is unique. In other words,

This is a very similar structure to the group .

Constructing Extension Fields

5.37 Field

The ring is a field if and only if is irreducible, i.e. it’s is with every polynomial in . This means that all elements are units (except ).

Example is a field, isomorphic to . There are no other extension fields on with irreducible polynomials that aren’t isomorphic to .

Some Facts about finite Fields *

When is a finite field, so is for a given polynomial (for irreducible).

5.38 Galois Fields

For every prime and every there exists an irreducible polynomial of degree in . In particular, there exists a finite field with elements.

5.39

There exists a finite field with elements if only if is a power of a prime. Moreover, any two finite fields of the same size are isomorphic.

Example: The fields is isomorphic to . We can see this is the case as has elements, , which we can basically map to as . Indeed in and which is in the isomorphism.

Generally, we can construct a field of order for prime by taking where is an irreducible polynomial of degree . Then has polynomials in it, as all of degree less than are coprime to , by definition of irreducible.

5.40 Cyclic Multiplicative groups

The multiplicative group of every finite field is cyclic.

This group has order and generators.

5.9 Application: Error-Correcting Codes

5.9.1 Encoding

5.35 -encoding function

An -encoding function for some alphabet is an injective function that maps a list of (information) symbols to a list of (encoded) symbols in called codeword:

We call the set the set of codewords.

5.36 Cardinality of the acode

An -error-correcting code over the alphabet with is a subset of of cardinality .

5.37 Hamming distance

The Hamming distance between two strings of equal length over a finite alphabet is the number of positions at which the two strings differ.

5.38 Minimum Distance

The minimum distance of an error-correcting code , denoted , is the minimum of the Hamming distance between any two codewords.

5.9.2 Decoding

5.39 Decoding function

A decoding function for an -encoding function is a function .

A good decoding function takes an arbitrary list of symbols and decodes it to the most plausible information vector. It should also be efficiently computable.

5.40 -error correcting

A decoding function is -error-correcting for encoding function if for any for any with Hamming distance at most from . A code is -error-correcting if there exists and with where is -error-correcting.

5.41 Minimum distance

A code with minimum distance is -error correcting if and only if .

5.9.3 Codes based on polynomial evaluation

5.42 Polynomial encoding function

Let for some and let be arbitrary distinct elements of . We then encode the values to the polynomial evaluation by with coefficients equal to the input: This code has a minimum distance of .

The polynomial (i.e. the coefficients, i.e. the message) can be interpolated from any values by Lagrangian interpolation: Two different codewords cannot agree at positions, otherwise they are equal. Thus they disagree in any positions (otherwise they’d agree in or more and thus they’d be equal).

Cheatsheet

Carriers and Operations for groups

| Yes | No | |

| No | Yes |

Rings and Fields

is a ring, a commutative ring, an integral domain and a field.

| Structure | , irred. | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Comm. Ring | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Integral Domain | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | ✓ | ✓ |

| Field | — | — | — | ✓ | — | — | — | — | — | ✓ | ✓ |

Properties of the different structures

Techniques

Polynomial division

See Week 10 DM Übung in Goodnotes

If the polynomial we are dividing by is not monic, i.e. we have divided by in , we can use the inverse of modulo to reduce it to one. thus .

Find Zero-Divisors in

We find the factorisation of . All multiplies of the factors of are thus zero-divisors.

Example: Consider the ring . We can write as . Thus all zerodivisors are the multiples of and :

- ,

- ,

Find GCD of two polynomials

We need to find a common factor using the roots (Nullstellen) method by trying all possible elements of the . Then we use the division with remainder to find the smaller elements and here we repeat the method used before.

We cannot just find all roots (Nullstellen) and let that be the gcd, as there might be a “double”-root: where the gcd is not but that we wouldn’t have noticed just by the roots.