4.1 Vector Spaces

4.1.1 Definition and Examples

4.1 Vector Space

A vector space is a triple where is a set (the vectors) and and are functions (scalar addition and multiplication). They satisfy the following axioms:

- = (commutativity)

- (associativity)

- vector such that for all

- for all such that

Note that: there is

- for all

- only one

- one unique for every

4.1.2 Subspaces

4.8 Subspace

Let be a vector space. A nonempty set is called a subspace of if the following two axioms of a subspace are true for all and all :

- (closure addition)

- (closure multiplication)

Note that the first condition is which must always be fulfilled!

4.9 Zero in all Subspaces

Let be a subspace of . Then .

Note that this is the case since we can set and get which has to be in all subspaces.

This means that for all subspaces, even if they’re orthogonal, .

4.11 Column Space is a subspace

Let be an matrix. Then the column space is a subspace of .

In the same way the rowspace and nullspace are subspaces.

4.14 Subspaces are vector spaces

Let be a vector space and a subspace of . Then is also a vector space, with the same and .

Note that is actually not a new vector space, but instead isomorphic to .

4.2 Bases and dimension

4.2.1 Linear combinations in vector spaces

We redefine the linear combination of a possibly infinite subset of vectors as a sum of the form where is a finite subset of .

A vector space is then closed under linear combinations. Every linear combination of is again in .

The set is called linearly dependent if there is an element such that is a linear combination of . Otherwise, is called linearly independent. The span of written as is the set of all linear combinations of .

4.2.2 Bases

4.18 Basis

Let be a vector space. A subset is called a basis of if is linearly independent and .

WARNING A basis is not always a set of vectors, it is a set of elements of . Thus for the subspace of diagonal matrices , the basis is made up of diagonal matrices.

Example: The set of unit vectors is the standard basis of .

Here the private non-zero is introduced as a non-zero entry in a vector which no other vector of the basis has. This is then used to justify that this vector is independent. Don’t use this in practice.

4.19 Basis of

The set of independent columns of is a basis of the column space .

Basis of

The basis of is . Since there is no vector, is vacously independent and since an empty sum yields .

Many bases

There are typically many bases for a vector space.

Example: Every set of linearly independent vectors is a basis of .

4.21 Finitely generated vector space

A vector space is called finitely generated if there exists a finite subset with .

Example: is not finitely generated for example.

4.22 Existance of a Basis

Let be a finitely generated vector space and let be a finite subset with . Then has a basis .

Proof We can iteratively remove elements from that are dependent until we are left with an independent basis.

4.2.3 Steinitz exchange lemma

4.23 Steinitz exchange Lemma

Let be a finitely generated vector space, a finite set of linearly independent vectors (note that does not need to span ) and a finite set of vectors with (but they mustn’t be independent). Then the following two statements hold:

- There exists a subset of size such that .

We can use the lemma to argue that there can’t be more than independent vectors in a space of dimension .

4.24 All bases have the same size

Two bases of (finitely generated) satisfy .

4.2.4 Dimension

4.25 Dimension

Let be a finitely generated vector space. Then the dimension of is the size of an arbitrary basis of .

4.2.5 Linear transformations between vector spaces

4.26 Linear transformation between vector spaces

Let be two vector spaces. A function is called a linear transformation between vector spaces if the following linearity axiom holds for all and all :

4.27 Bijective linear transformations preserve bases

Let be a bijective linear transformation between vector spaces and . Let be a finite set of size , and let be the transformed set. Then . Moreover, is a basis of if and only if is a basis of . We therefore also have .

This holds because of the bijectivity of the linear transformation.

Further, if there is one such bijective transformation, then we call the vector spaces isomorphic and an isomorphism between and (Definition 4.28). All -dimensional vector spaces are isomorphic.

4.29 Basis writes each vector as unique linear combination

Let be a basis of . For each , there are unique scalars such that

4.2.6 Computing a vector space

4.30 Less than vectors do not span

Let be a finitely generated vector space. Let be a finite subset of size . Then .

Using this lemma we can now state that computing a vector space means finding a basis. No smaller set of vectors can fully describe a vector space.

4.3 Computing the three fundamental subspaces

4.3.1 Column Space

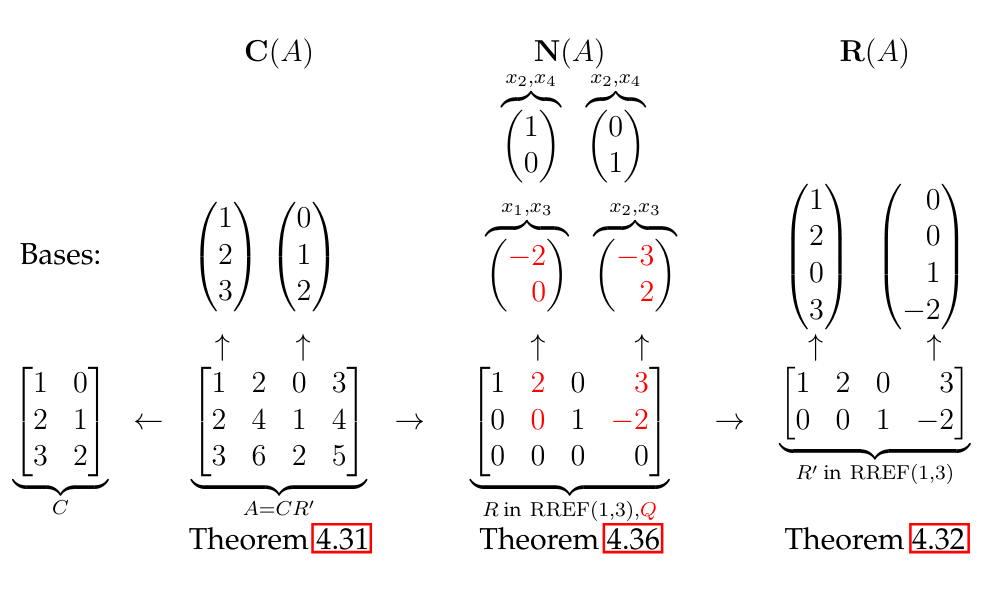

4.31 Basis of from RREF

The independent columns in the RREF form of matrix are a basis of the column space and in particular:

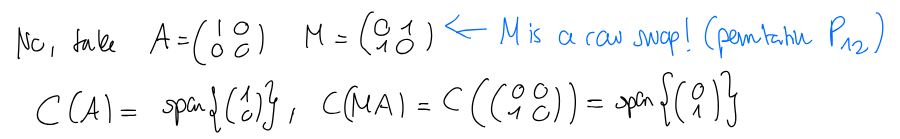

It is not true that , see for example:

4.3.2 Row space

4.32 Basis of Row space

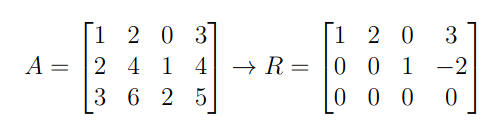

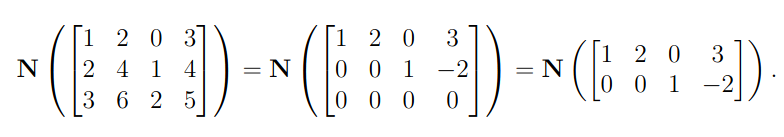

The first columns of where is the RREF of form a basis of the row space (the non-zero rows). In particular

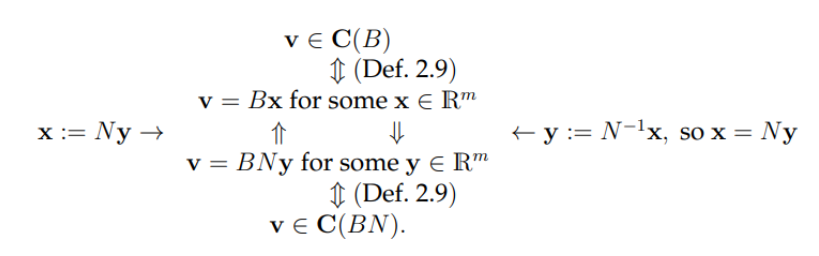

This works because as noted before, multiplying by and invertible matrix M does not change the row-space of MA on the left.

Intuitively, we are multiplying on the left by invertible matrices and thus basically take linear combinations of the rows of . Thus the row-space stays the same.

Proof:

which is true because of this:

4.33 Row rank = column rank

For an matrix, we have

4.34 Rank bound

where is the rank of .

4.3.3 Nullspace

Same as with the row-space has the same nullspace as : .

How to find a basis:

Note that we can remove the zero-rows because regardless of .

Note that we can remove the zero-rows because regardless of .

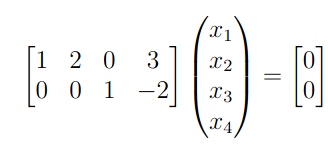

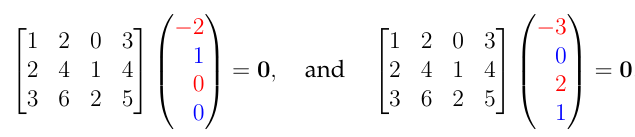

We now want to solve for :

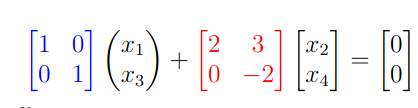

We seperate the matrix into the identity and the “rest”. Note that for this we take columns 1 and 2 as they form the 2x2 identity.

Which we can transform into:

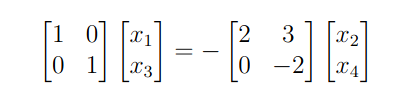

Which we can transform into:

As on the left we have the identity, we reduce it to just the x vector, which gives us a system in two equations and 4 unknowns.

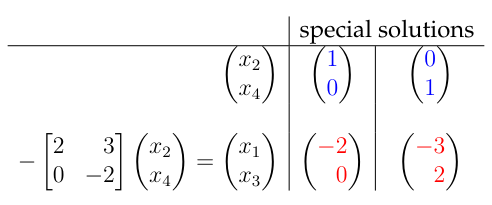

We choose two special solutions (independent) and then plug in the values into our equations to find the rest.

This gives us a basis of the nullspace as we get two linearly independent vectors in there and it has dimension 2. We call these particular solutions.

We choose two special solutions (independent) and then plug in the values into our equations to find the rest.

This gives us a basis of the nullspace as we get two linearly independent vectors in there and it has dimension 2. We call these particular solutions.

4.36 Dimension Null Space

4.36 Dimension Left Null Space ( )

See sheet 7 where this is stated.

Summary

4.4 The solution space of

4.37 Solution space of a system

Let be an matrix and . The set is the solution space of

If , is unfortunately not a subspace of , because it doesn’t contain the zero vector!

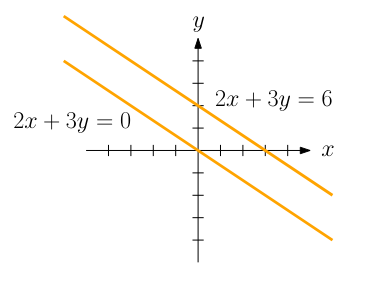

If , the the solution space is “shifted” of the origin:

We can “fix” this by instead looking at the line through the origin. as we search for the zeros. We thus first find the nullspace, and then shift it by an arbitrary solution of .

4.38 Shifting nullspace

Let be some solution of . Then

4.4.1 Affine Subspaces

We call the solution space of an affine subspace if .

4.4.2 Number of Solutions

4.39 Dimension of solution space

If has a solution, then has dimension , where

If has rank , then has a solution for every (equivalent to saying that ). We call solvable (invertible is a special case of this).

We list all possibilities:

- If ( is square), the system is called square. Typically solvable.

- If (A is a wide matrix), the system is called underdetermined. There are typically solvable.

- If (A is a tall matrix) the system is called overdetermined. Typically not solvable. (Undetermined because there are more variables that equations.)