6.1 Least Squares Approximation

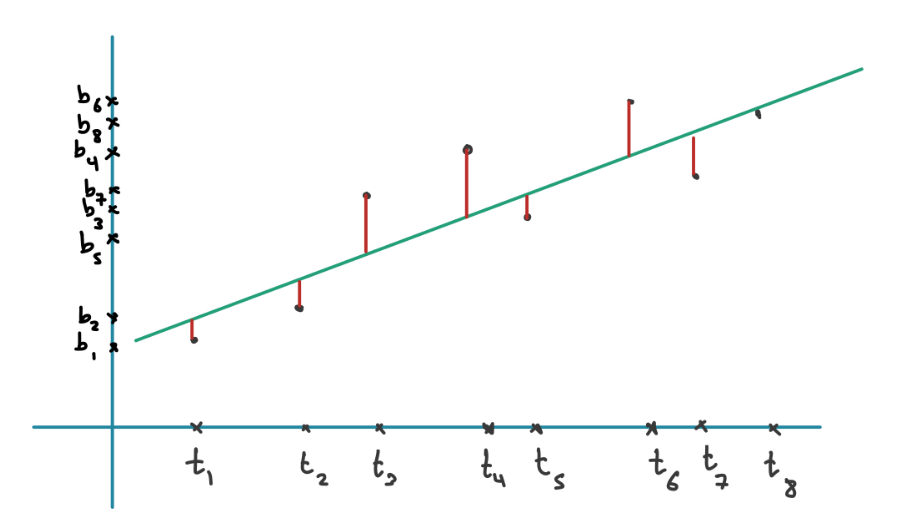

One case in which usually has no solutions is when trying to fit a line to a set of measurements or datapoints. We can then try to use a least squares approximation to find a best-fitting line.

6.1.1 Minimiser is solution to the normal equations

A minimiser of is also a solution of . When has independent columns the unique minimiser of is given by

Notice that being minimal is equivalent to asking to be the projection of onto (then we minimise the error). Thus we can solve for (which when multiplied with gives us the projection) by using the projection, without the final on the left, which gives us the above equation.

The line here can be represented by the equation . We want to find and that minimise the sum of squares of the error of the fitted line: which in Matrix vector notation gives where and

6.1.2 Independent columns of

The columns of the matrix defined before are linearly dependent if and only if for all .

As all datapoints are unique in time (can’t have two points at one time) this always holds.

6.1.3

If the columns of are pairwise orthogonal, we get a diagonal matrix which is very easy to invert. We can convert any to have orthogonal columns by making sure that the sum of all the , which can be achieved by shifting the graph on the x-axis.

We can also try to fit any other equation, not just a line here. A parabola could be used by adding a third column to which contains and adding .

6.2 The set of all solutions to a system of linear equations

We know that , there exist and such that and as are orthogonal complements.

6.2.1 Unique solutions

Let . Let . We have that

Proof This is because have unique decompositions into the two fundamental subspaces. and from this follows that .

6.2.2 Unique solution to a system

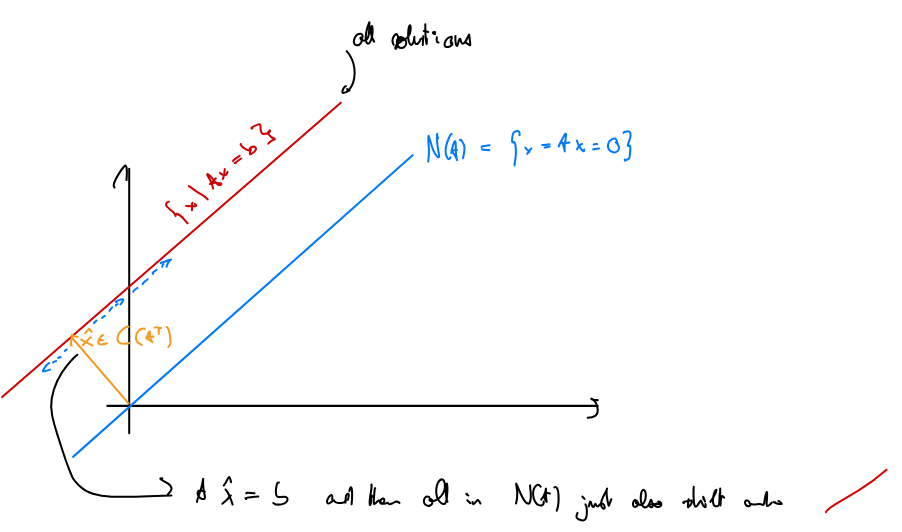

Suppose that . Then where is unique such that .

This means that if there’s more than one solution to the system (i.e. the nullspace is not ), then the set of all solutions is a specific solution + the entire nullspace.

6.2.3 Unique in

Suppose that . Then there exists a unique vector such that

The empty solution

We now only need to analyse the case where the given system of linear equations has no solutions: .

This is difficult as proving a negative in this case means exhausting the entire search space (which is infinite) or proving it by using something smarter.

We can issue a “certificate” which proves that a system has no solution.

6.2.4 Proving no solutions

Note that we don’t need it to be , it just has to be .

In words: our LSE does not have any solutions if and only if there exists a vector that is orthogonal to all columns of but not orthogonal to .

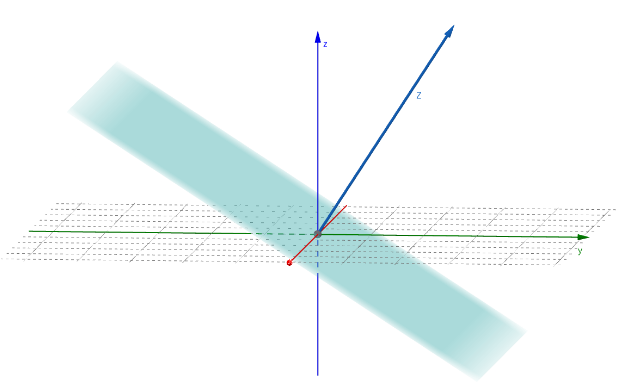

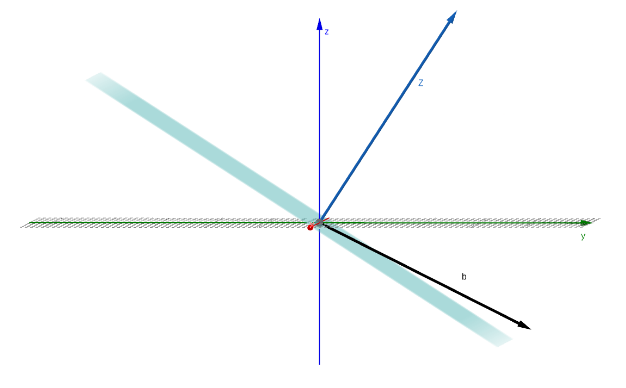

The blue vector is orthogonal to all in , the blue subspace.

The blue vector is orthogonal to all in , the blue subspace.

If is not orthogonal to , this means that it cannot possibly be in the subspace, it must be slightly above/below it. Therefore and thus there’s no solution.

If is not orthogonal to , this means that it cannot possibly be in the subspace, it must be slightly above/below it. Therefore and thus there’s no solution.

Proof:

- Verify that is impossible:

- If and then

- We now want to show that if :

- (there are no solutions) (there is an error,

- Thus and

- but we can rewrite and thus

- we know the first term is as as they are in orthogonal subspaces

- the second term is as it’s .

- Thus

- (there are no solutions) (there is an error,

Example:

- The system is then $$ D = { z \in \mathbb{R}^2 \ | \ z_1 + 2z_2 = 0, 2z_1 + 4z_2 = 0, -z_1 - 2z_2 = 0, z_1 = 1 } $$$P = \emptysetD \neq \emptysetz = (1, -\frac{1}{2})^\top \in D$.

Applications:

- If our matrix had linearly independent rows, then there would be solutions for all points in . Since the rows are linearly independent, the only solution to is . Hence . Thus there is always a solution for the .

- We can also show that a vector is linearly independent from a set of vectors . We just put them into the matrix equation . If there is no solution, is independent. But to show the system has no solutions, we need our new formula.

6.3 Orthonormal Bases and Gram-Schmidt

6.3.1 Orthonormal vectors

Vectors are orthonormal if they are orthogonal and have norm . In other words, for all where is the Kronecker delta ().

Thus all vectors are pairwise orthogonal and all of them have norm : .

6.3.3 Orthogonal Matrix

A square matrix is orthogonal when . In this case

- The columns form an orthonormal basis for .

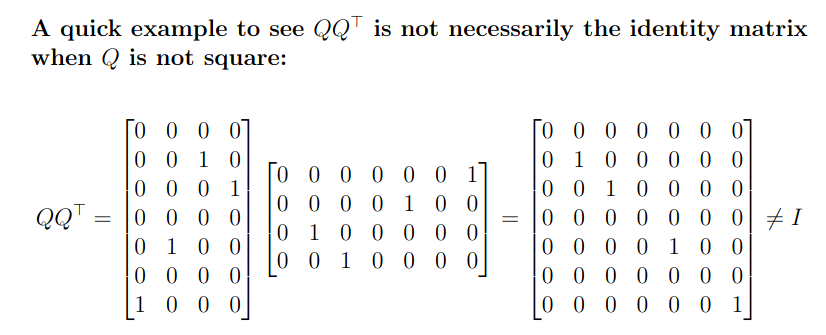

Note that when is not square, still holds, but doesn’t necessarily.

Examples:

- 2x2 Rotation matrices are orthogonal

- Permutation matrices are orthogonal

6.3.6 Orthogonal matrices preserve norm and inner product

Orthogonal matrices preserve the norm and inner product of vectors. In other words, if is orthogonal, then, for all

Proof: . since . We can use this same argument for the first equality thus and note that and thus it suffices to show that the squares are equal.

6.3.7 Projections with Orthogonal matrices

Let be a subspace of and be an orthonormal basis for . Let be the matrix whose columns are the ‘s. Then the projection matrix that projects to is given by and the least squares solution to is given by .

This is the case because simplifies to in the case where our is orthogonal. Thus simplifies to .

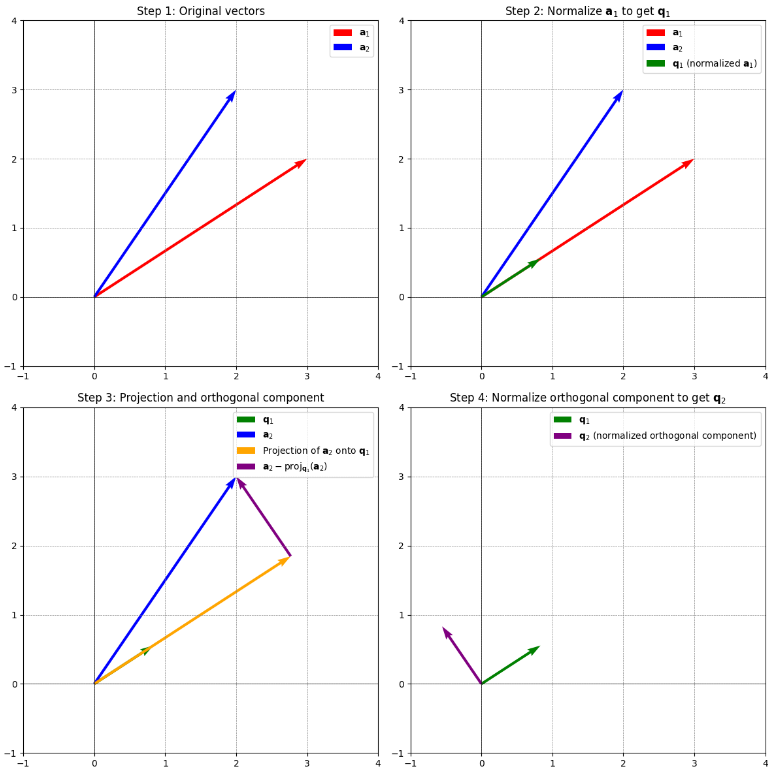

How to get an Orthonormal Basis: Gram-Schmidt

Algorithm to normalize two vectors: (Gram-Schmidt with 2 only)

- Normalise to get .

- Project onto using . Since is normalised (norm 1), we have .

- Subtract the projection of on we just calculated from to get .

- Normalise to get .

We project onto and then subtract that since we want to remove the part of that is in the direction of to get orthogonal vectors.

We project onto and then subtract that since we want to remove the part of that is in the direction of to get orthogonal vectors.

Algorithm (Gram-Schmidt):

- For set \begin{align*} q'_k =& a_k - \sum_{i = 1}^{k - 1} (a_k^\top q_i)q_i \\ q_k =& \frac{q_k'}{||q'_k} \end{align*} Linearly dependent case (not in lecture) (i.e. the vectors don’t form a basis) Since in a linearly dependent set of vectors one of them is a linear combination of the previous ones, you’d get in the subtraction step for it. By excluding those ‘s you’d still get an orthonormal basis.

QR-Decomposition

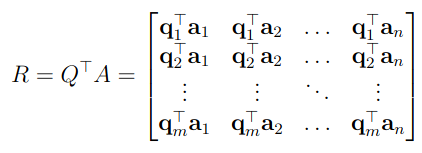

For an with linearly independent columns, let be the result of G-S. Then define . is upper triangular because each is orthogonal to every for (all after it). Note that not necessarily square and thus not invertible.

You can see here, since are by construction orthogonal to thus , all entries below in the first column are . The same goes for all entries below in the second column.

You can see here, since are by construction orthogonal to thus , all entries below in the first column are . The same goes for all entries below in the second column.

is the projection on the span of the ‘s and thus also on the ‘s (). Thus and therefore .

6.3.10 QR-Decomposition

Let be an matrix with linearly independent columns. The QR decomposition is given by where

- is an matrix with orthonormal columns (they are the output of Gram-Schmidt)

- is an upper triangular matrix given by .

6.3.11 R is upper triangular and invertible

The matrix defined in 6.3.10 is upper triangular and invertible. Moreoever, and hence is well defined.

We have since has independent columns and thus . Thus (square) must be invertible.

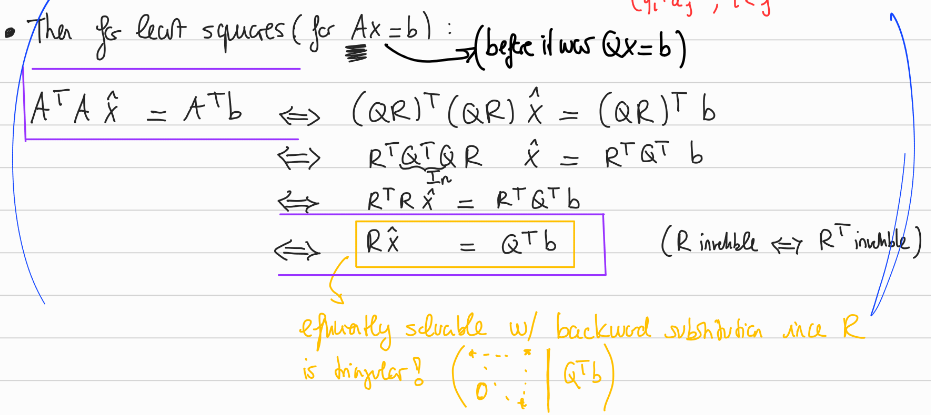

Fact 6.3.12 The QR decomposition greatly simplifies calculations involving Projections and Least Squares:

- Since then projetions on can be done with : .

- The least squares solution to denoted is defined as a solution of the normal equations Furthermore and thus Since is invertible we can simplify this to which can efficiently be solved by back substitution since is a triangular matrix.

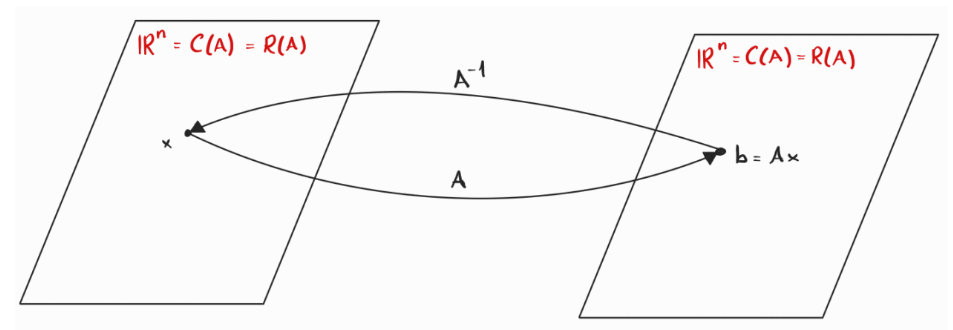

6.4 Pseudoinverse

Given , we can find by applying if is invertible: . But if is not invertible, we want to find a matrix which accomplishes a similar job as the actual inverse: should give us .

Prelude

is a linear transformation with . The inverse should be a function from with .

If is invertible, then must be square so we have a mapping from :

This is bijective, it perfectly reverses.

This is bijective, it perfectly reverses.

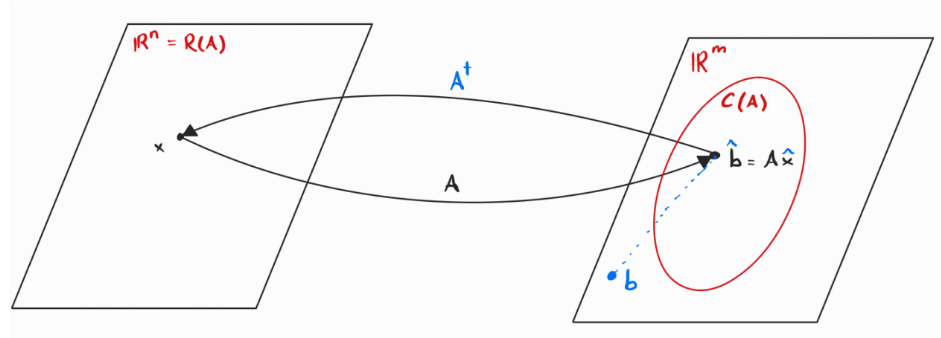

If with independent columns (full column-rank), we can visualise as such: The column space is just part of the whole .

We first have to project into , before we can invert it.

By inverting, we map back to , i.e. we find an that brings us closest to , which is exactly Least Squares.

The column space is just part of the whole .

We first have to project into , before we can invert it.

By inverting, we map back to , i.e. we find an that brings us closest to , which is exactly Least Squares.

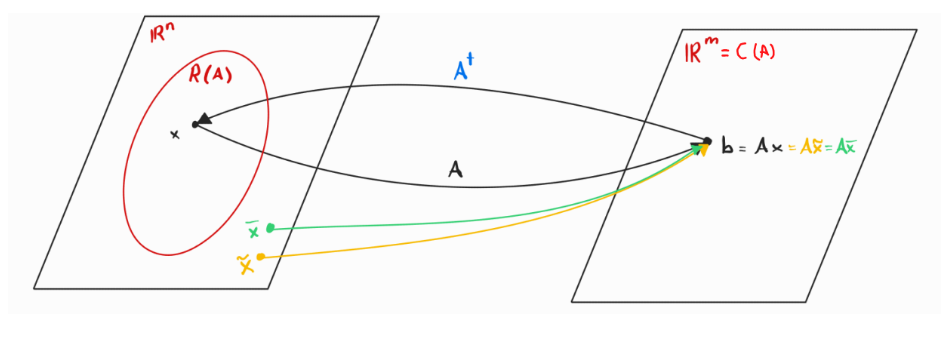

If with independent rows (full row-rank), we can visualise as such:  There are multiple that map to via , and we have to find one to which we invert. We pick one with the smallest norm minimal.

By Lemma 6.4.5 we know that the smallest such is an . Since does not have full column rank, has a non-trivial nullspace, and thus the solution space of is . If we take the unique vector in , we basically set to , thus making sure the norm is minimal.

There are multiple that map to via , and we have to find one to which we invert. We pick one with the smallest norm minimal.

By Lemma 6.4.5 we know that the smallest such is an . Since does not have full column rank, has a non-trivial nullspace, and thus the solution space of is . If we take the unique vector in , we basically set to , thus making sure the norm is minimal.

If has neither full column nor full row-rank, we have to solve both problems at once. We then decompose (with full column-rank and full row-rank). Then .

6.4.1 Definitions

6.4.1 Pseudoinverse for matrices of full column rank

For with , we define the pseudo-inverse as

6.4.2 Left Inverse

For with , the pseudoinverse is a left inverse of , meaning

Proof: Since has full column rank, invertible and then .

6.4.3 Pseudoinverse for matrices with full row rank

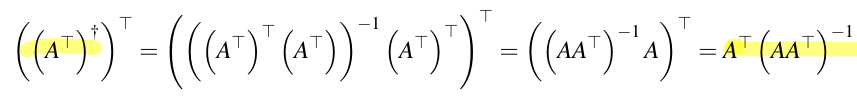

For with , we define the pseudo-inverse as

For an with full column-rank, we basically define, as the transpose of the pseudoinverse of the transpose:

6.4.4 Right inverse

For with , the pseudo-inverse is a right inverse of :

Proof Since has full column rank, is invertible: .

Since for full row rank there are many possible solutions, the pseudoinverse is choosing the one with the smallest norm such that . Since each solution is with and , the pseudoinverse chooses an with no nullspace component to get the smallest norm. Notice the at the front of the definition. This means that is in the row-space: exactly what we want!

6.4.5 & 6.4.6 Unique Solution for full row rank

For any matrix and a vector , the unique solution to is given by the vector that satisfies .

For a full row rank matrix , the unique solution is given by the vector .

Proof By Lemma 6.4.5 we only need to show that satisfies and that .

- for some thus

6.4.7 Pseudoinverse for all matrices

For with and CR decomposition , we define the pseudoinverse as

We can rewrite this as .

6.4.8 For any

Given and a vector , the unique solution to such that is given by .

6.4.9 Full Rank Factorisation

For with , let and such that . Then

6.4.10 Pseudoinverse Conditions

is a pseudoinverse if it satisfies the following conditions:

- is symmetric (i.e. ). It is the projection matrix on .

- is symmetric (i.e. ). It is the projection matrix on .

Nullspace of and : We have . Intuitively this holds as (we pick the minimal ). Thus anything orthogonal to the subspace is projected to : we have . We conclude that .