The determinant of a matrix can be understood as the volume of the unit-cube after transformation. It can be stretched, squished or be reduced to a point (non-invertible matrix).

(Informally) The signed volume of this parallelepiped gives us the determinant.

7.1 Definition from Properties

Properties of the determinant

- if linearly dependent columns.

- Exchanging two rows flips the sign of the determinant.

- Subtracting two rows does not change the . (we can use G-J (only row subs/adds) to simplify calculations…)

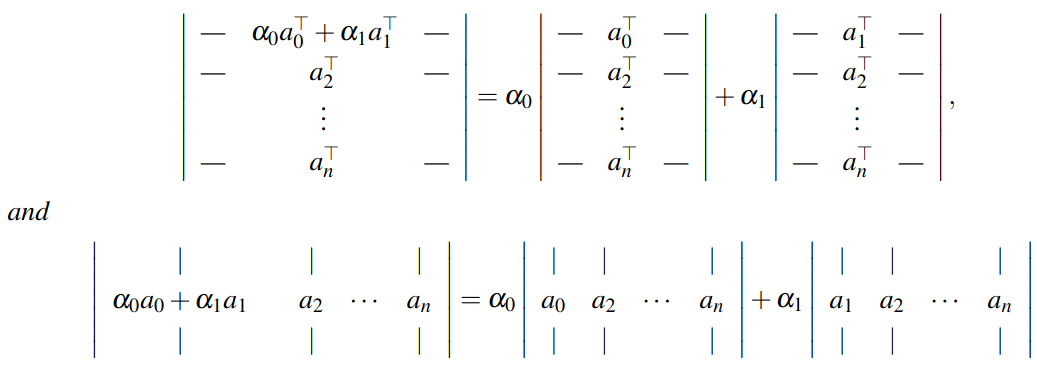

Multilinearity

The determinant preserves “multilinearity”. This means that changing only a single row will preserve the rest of the determinant (it’s linear for each row):

Example: For a matrix, fixing the second column: Which gives us .

Important: Multilinearity does not mean . Instead: because scaling affects all columns simultaneously.

Determinant of Upper-Triangular

The of upper (or lower) triangular is .

Using Gauss-Jordan to simply calculations

Because the determinant of an Upper- (or Lower)-Triangular matrix is the product of the pivots, we can often use G-J-Elimination to make computation easier.

We cannot exchange rows (without keeping track of the sign), nor can we multiply rows (without multiplying the determinant by that same factor) in the end.

7.2 General Case (def. using Permutations)

7.2.1 Sign of a Permutation

Given a permutation of elements, it’s sign can be -1 or 1. The sign counts the parity of the number of elements that are out of order (inversions) after applying the permutation.

The permutation , defined as , , , , we have the pairs for . For all these pairs , except for which gives . Thus .

This can also be counted as the parity of the number of row swaps necessary to get back to the identity.

Properties of the sign

- The sign of a permutation is multiplicative: .

- For all , exactly half of the permutations have sign and the rest have sign .

7.2.3 Determinant formula

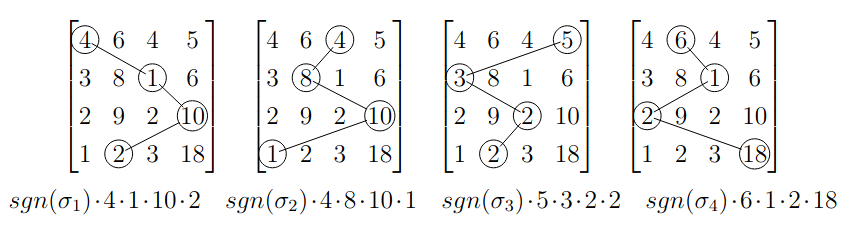

Given a square matrix , the determinant is defined as: where is the set of all permutations of elements (of which there are ).

Visualised:

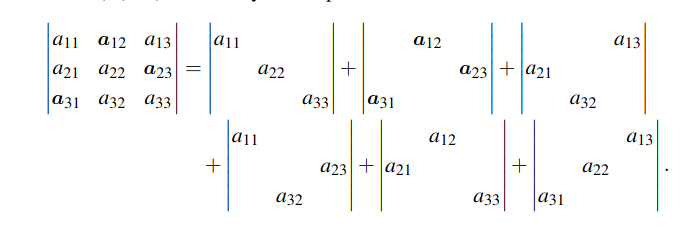

Examples In a matrix, there are permutations, the identity and the inversion. From this we can get the formula for matrices.

Note that this is the multilinear decomposition These are the terms we get in the sum for according to the above formula. Each of them is one of the permutations applied to the matrix.

We then want to find the sign of the permutation: number of row exchanges to get back to a diagonal.

Note that this is the multilinear decomposition These are the terms we get in the sum for according to the above formula. Each of them is one of the permutations applied to the matrix.

We then want to find the sign of the permutation: number of row exchanges to get back to a diagonal.

7.2.4 Properties of the Determinant

- Given a permutation matrix corresponding to a permutation , then (this is as is also an orthogonal matrix, see 3.). We sometimes write .

- Given a triangular (either upper or lower) matrix , we have in particular, .

- If is an orthogonal matrix then This makes sense as there is no scaling in an orthogonal matrix.

Intuition:

- For the permutation matrix, each row contains only one entry: a . Thus the only permutation in the product that doesn’t have a factor is the permutation corresponding to the matrix itself. The product is thus we get .

- For a triangular matrix, if we choose an element off the diagonal, we are then forced to choose one in the s thus making that factor . The only valid permutation is thus the , which means we just multiply the diagonals.

- As is orthogonal, we don’t scale (preserves ) thus the unit cube is just turned, not scaled.

Note that for a triangular matrix, if one of the diagonal entries is zero, the determinant is also 0 (as it’s in the product). This matches what we observed before.

7.2.5 Determinant of the Transpose

Given a matrix , then

Proof Idea: This follows from the fact that the inverse of a permutation has the same sign, and transposing is the same as doing the inverse permutation. This also means that we can choose a row or a column when doing cofactor calculations.

7.2.6 Determinant Properties 2

- A matrix is invertible if and only if

- Given matrices , we have

- Given a matrix such that then is invertible and

Intuitively, these properties make sense if you think of the determinant as being the volume of the unit cube.

- If the unit cube collapses to have 0 volume (i.e. ) then we lost a dimension and cannot be invertible.

- If we multiply first by then the unit cube will be stretched the same way as if we did both at once.

- If shrinks the unit cube and inflates it back to the unit dimensions then the ratio of the changes is .

Property from the sheet 10

For and we have .

7.3 Cofactors, Cramer’s Rule and Beyond

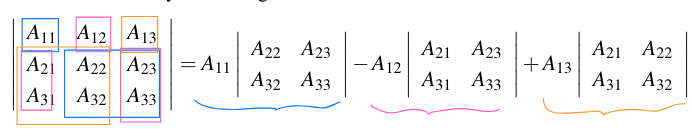

7.3.1 Cofactors

Given for each let denote the matrix obtained by removing row and column from . Then we define the co-factors of as

Note that the sign basically draws a + - + - + - grid on the matrix: We can then express the determinant as a sum of these co-factors: in which we multiply the cofactor of every element by the element itself, as is clear in the example above for a 3x3.

We can also define the inverse in terms of co-factors now: or rewritten as . Note that this is not an efficient way to find the inverse.

7.3.6

If is a matrix and is a permutation that swaps two elements (i.e. ) then corresponds to swapping two rows of then .

7.3.7 Determinant is Linear

The determinant is linear in each row (or each column). In other words for any and we have

Tricks

Constraints on Permutations

During the determinant calculation we have to look at all possible permutations and sum those. If , i.e. we venture off the diagonal (identity permutation), we’re going to have to venture off the diagonal for another as well: .

If we have a matrix , the only permutation that doesn’t produce a product is the permutation.