5.1 Orthogonality

5.1.1 Orthogonal Subspaces

Two vectors are called orthogonal if . Two subspaces and are orthogonal if for all and , the vectors and are orthogonal.

5.1.2 Subspaces Orthogonal if Basis is Orthogonal

Let be a basis of subspace . Let be a basis of subspace . and are orthogonal if and only if and are orthogonal for all and .

As all vectors are pairwise linearly independent, their set is also linearly independent.

5.1.3 Basis of Subspace together form basis of .

Let and be orthogonal subspaces of . Let be a basis of subspace . Let be a basis of subspace . The set of vectors are linearly independent.

We can use this Lemma to get the basis of the subspace , which is then indeed also a subspace of . This sum of orthogonal vectors is called the Minkovsky-Sum!

5.1.4 Properties of orthogonal subspaces

Let and be orthogonal subspaces. Then (as all subspaces contain the vector).

If and , then .

5.1.5 Orthogonal Complement

Let be a subspace of . We define the orthogonal complement of as

This is also a subspace of . Therefore, the concept of orthogonal subspaces allows us to decompose the space into a subspace and it’s complement (these being the nullspace of and the row space of ).

5.1.6 Decomposition of

Let be a matrix.

As we know that if then . Thus they add up to the whole space!

5.1.7 Orthogonal subspace properties

Let be orthogonal subspaces of . Then the following statements are equivalent.

- Every can be written as with unique vectors ,

5.1.8 Orthogonality cancels out

Let be a subspace of . Then

This allows us to rewrite Theorem 5.1.6:

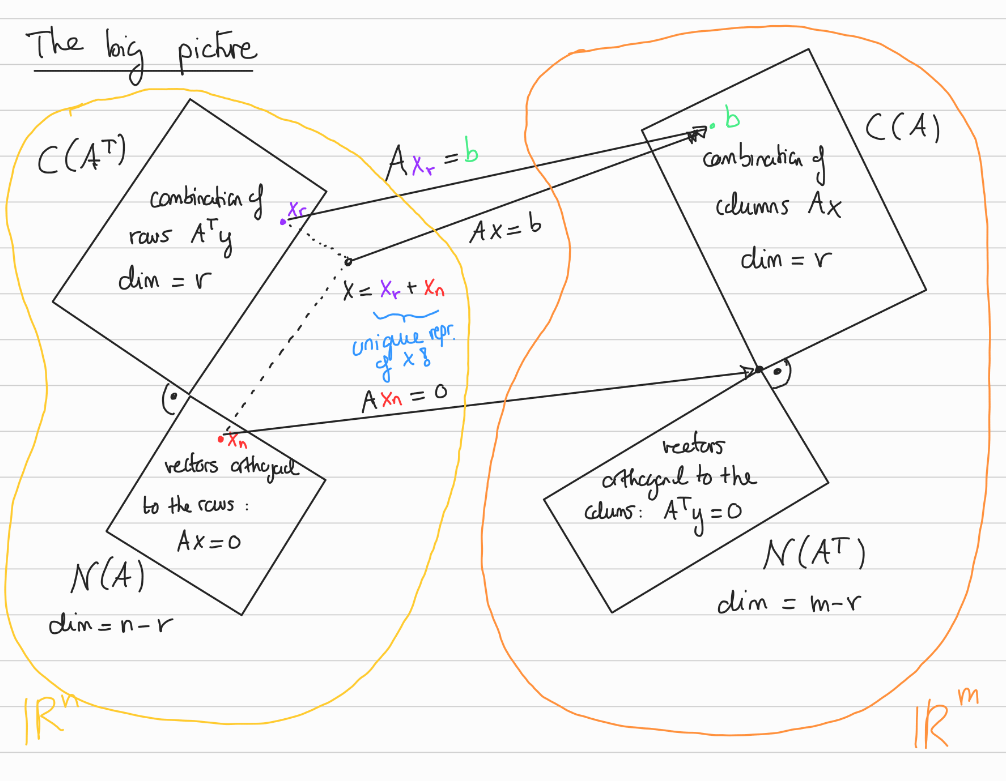

5.1.8 Four fundamental Subspaces

Let .

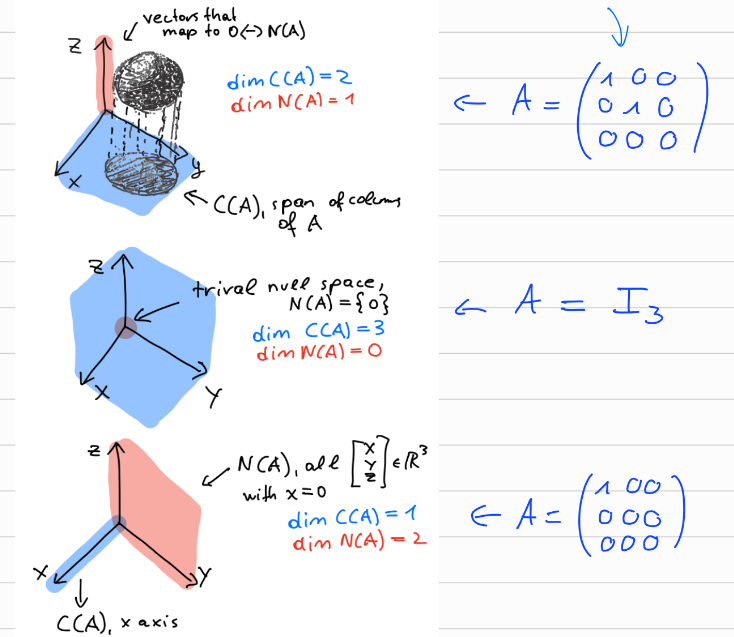

We can visualise the four fundamental subspaces in the following way:

Consequences: Recall that the complete solution to (“all ‘s st “) where is a particular solution (assuming the system is feasible).

You can show that is also equal to , where and and where is unique (i.e. such a particular solution always exists and is unique) (See Sabatino Notes Week 9 for Proof.)

5.1.10 and

Let . Then and .

This holds because:

- if then .

- if then , which means

5.2 Projections

If a system has no solutions (because is not invertible, i.e. ) can we find a such that the error is minimal - basically the next best solution?

This usually happens when we have more equations than variables (i.e. each is being “overdetermined”) .

5.2.1 Projection of a vector onto a subspace

The projection of a vector onto a subspace (of ) is the point in that is closest to . In other words

Where , with the error.

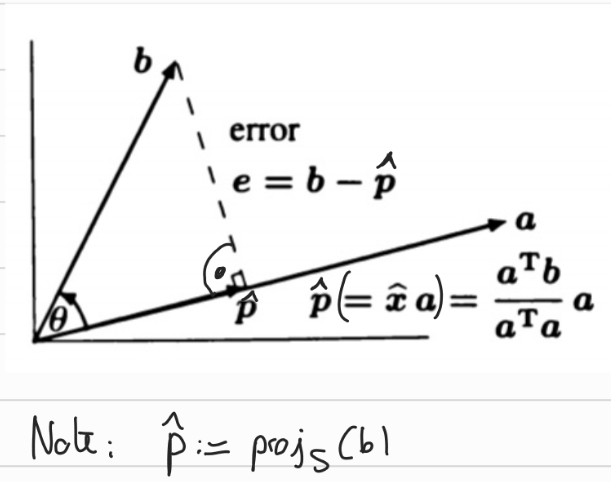

The one-dimensional case

We can clearly see that the error vector in 2d is orthogonal to the projection by geometric intuition.

5.2.2 Projection in 2d formula

Let . The projection of on is given by This minimiser is unique.

And indeed if we substitute we find that the error vector is indeed orthogonal to .

Note that if we want to find the projection of a vector , then the projection simply returns , as is already on the line (subspace).

General Case

5.2.3 Projection is well defined

The projection of a vector to the subspace is well defined. It can be written as where satisfies the normal equations

INFDEF

If is invertible, we have a unique solution that satisfies the equation:

5.2.4 invertible has indep. columns

is invertible if and only if has linearly independent columns.

5.2.5 Projection Matrix

Let be a subspace in and a matrix whose columns are a basis of . The projection of to is given by where is the projection matrix.

Note the condition for the columns to be a basis - this forces them to be independent, which means invertible by Lemma 5.2.4.

IMPORTANT It may look like we can simplify the expression for the projection matrix . This is not the case as is only the case if itself is invertible. But if is invertible, it spans anyways and any projection is simply the point itself. This is beautifully reflected in the fact that if we simplify then we simply get .

5.2.6

- If then by definition. This requires us to have that .

- Let be the orthogonal complement of and the projection matrix onto .

- Then is the projection matrix that maps to .

- Proof Idea: Since with Thus

- Note that - as it should be - we have that