We know from 8. Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors that given EV we can build a basis of if the matrix has distinct real eigenvalues.

What happens in the case where some eigenvalues are repeated? Can we still build a basis of ? Example:

Both matrices have the eigenvalue with algebraic multiplicity 2. But has with geometric multiplicity as well, thus the multiplicities match and we can build a basis as we’ll see later in a theorem. “In general when there is an eigenvalue with algebraic multiplicity larger than 1, it can be that is of large enough dimension to find enough linearly independent eigenvectors.”

From EWs to Diagonalisable Matrices

Whenever we have a basis of that consists of real eigenvectors of we can change the basis of the row and column space to view as a diagonal matrix, which is then easy to invert.

9.1.1 Diagonalisation

Let . Suppose that has eigenvectors that form a basis of . For let be the eigenvalue associated to . Let be the matrix whose columns correspond to the eigenvectors . Then, where is a diagonal matrix with (and for all ).

Proof Since forms a basis, the vectors are independent and exists. We then verify that . For any the -th column of the matrix is given by since . Since for any is the -th column of we are done.

9.1.2 Diagonalisable Matrix

A matrix is called diagonalisable if there exists an invertible matrix such that where is a diagonal matrix.

9.1.3 Complete set of real eigenvectors

If given a matrix we can build a basis of with eigenvectors of we say that has a complete set of real eigenvectors.

Examples A diagonal matrix has eigenvalues which are the diagonal entries of and a full set of eigenvectors . Note distinct eigenvalues imply distinct vectors, distinct vectors don’t imply distinct eigenvalues. There can be an eigenvalue with geometric multiplicity such that it’s eigenvectors span more than dimension.

Example The eigenvalues of a triangular matrix are the diagonals. However, it might not have a complete set of real eigenvectors. does not for example.

9.1.6 EVs, EWs of a Projection Matrix

Let be the projection matrix onto the subspace . Then has two eigenvalues, and , and a complete set of real eigenvectors.

Proof Let be the dimension of . Let be an orthonormal basis of and be an orthonormal basis of . (thus EW 1) and (thus EW 0). The geometric multiplicities match the algebraic ones here, thus has a complete set of real eigenvectors.

9.17. Similar Matrices

We say that and are similar matrices if there exists an invertible matrix such that .

9.1.8 Similar Matrices share Eigenvalues

Similar matrices and have the same eigenvalues. The matrix has a complete set of real eigenvectors if and only if does.

Proof EW, EV pair for matrix iff .

9.1.10 Geometric Multiplicity

Given a matrix and an eigenvalue of we call the dimension the geometric multiplicity of .

9.1.11 Geometric and Algebraic Multiplicities match

A matrix has a complete set of real eigenvectors if all its eigenvalues are real and the geometric multiplicities are the same as the algebraic multiplicities of all it’s eigenvalues.

Example has eigenvalue with geometric multiplicity () and algebraic multiplicity (As the characteristic polynomial of , with that repeated times).

9.2 Symmetric Matrices and the Spectral Theorem

9.2.1 Spectral Theorem

Any symmetric matrix has real eigenvalues and an orthonormal basis of consisting of it’s eigenvectors.

9.2.2 Diagonalisation

For any symmetric matrix there exists an orthogonal matrix (whose columns are the eigenvectors of ) such that where is a diagonal matrix with the eigenvalues of in it’s diagonal (and ).

This decomposition is called an eigen-decomposition.

9.2.4 Rank of Symmetric Matrix

The rank of a real symmetric matrix is the number of non-zero eigenvalues (counting repetitions).

9.2.5 Rank of any A

For general non-symmetric matrices, the rank is so it’s minus the geometric multiplicity of .

9.2.6 Recover A from EVs, EWs

Let be a real symmetric matrix and let be an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors of (the columns of matrix in diagonalisation) and the associated eigenvalues. Then

We now show some Lemmas useful for the proof of the Spectral Theorem.

9.2.7 Orthogonal EVs for distinct EWs

Let be a symmetric matrix and be two distinct eigenvalues of with corresponding eigenvectors . Then and are orthogonal.

Proof Thus must be .

9.2.8 All EVs of Symmetric Matrices are Real

Let be a symmetric matrix and be an eigenvalue of , then .

Proof be EV of . Thus we have . Since is symmetric we have . Since , then and so thus .

9.2.9

Every symmetric matrix has a real eigenvalue .

Proof of the Spectral Theorem

The Spectral Theorem is proven by induction . For any there are orthogonal eigenvectors of . We want to show that this holds for .

B.C.: For : Since symmetric, we have a real eigenvalue and thus vector, which we normalise to get orthogonal eigenvectors.

I.H.: We assume the statement and show that it holds for .

I.S.: We have orthonormal eigenvectors and he respective EWs. We also have an orthonormal basis of the orthogonal complement to the span of .

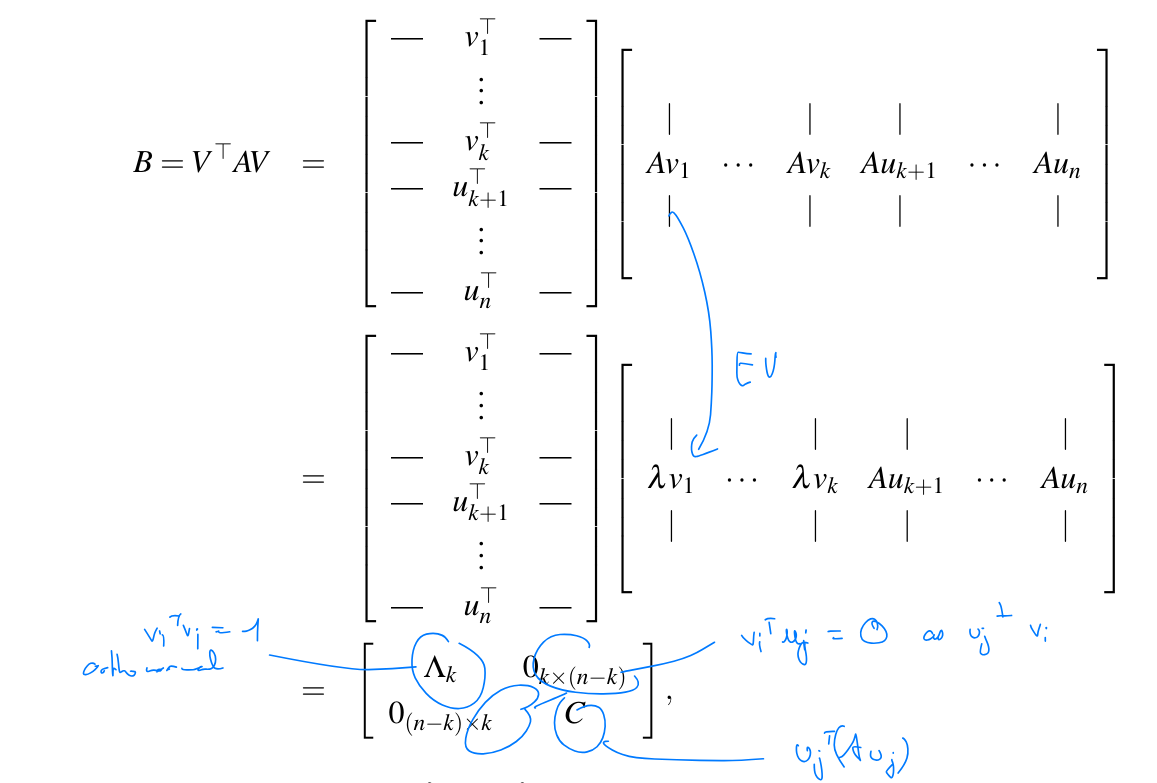

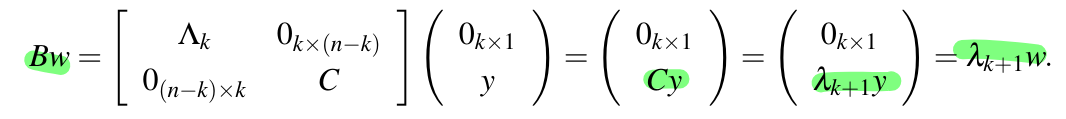

We define the matrix as and then define .

We note that is a symmetric matrix. Therefore it has one real eigenvalue and a real eigenvector . We define which means we’re basically lifting into .

We have  Define . Since is orthogonal it has inverse thus .

Thus . Thus is an eigenvector of .

Define . Since is orthogonal it has inverse thus .

Thus . Thus is an eigenvector of .

Applications

9.2.10 Rayleigh Quotient

Given a symmetric matrix the Rayleigh Quotient defined for , as attains it’s

- maximum at

- minimum at

where and are respectively the largest and smallest eigenvalues of and and their associated eigenvectors.

Proof: It is easy to see that and . See .

Show that, for all we have . We write in it’s sum form where form an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors of and are the associated eigenvalues: Since for all we have that, for all , Collecting all these inequalities we get To conclude the proof note that, since the ‘s are orthonormal, the matrix with the ‘s as columns is orthogonal (it doesn’t affect scalar products) and thus and so .

9.2.11 PSD, PD

A symmetric matrix is Positive Semidefinite if and only if for all . A symmetric matrix is Positive Definite if and only if for all .

Example is PD. Any diagonal matrix (with diagonal entries) is always PD.

PSD and PD matrices are closed under addition

If we take PSD (or PD) then is also PSD (or PD).

9.2.3 Gram Matrix

Given vectors we call their Gram Matrix the matrix of inner products If is the matrix with columns then is the Gram matrix of .

We sometimes call the a Gram Matrix of (abuse of notation). For is and .

9.2.15 Shared EWs

Given a real matrix , the non-zero eigenvalues of are the same ones of . Both matrices are symmetric and PSD.

Proof and are PSD.

Since and are symmetric, they have a full set of real eigenvalues and orthogonal eigenvectors (see Spectral Theorem and Diagonalisation). Shared EWs: For we get and thus EV and is an EW of . Orthogonality: For we have

9.2.16 Cholesky Decomposition

Every symmetric PSD matrix is a Gram Matrix of an upper triangular matrix . is known as the Cholesky Decomposition.

Thus all PSD matrices are decomposable as with upper triangular!

Proof Since is symmetric PSD, we can say with diagonal matrix with EWs in the diagonal. Since is PSD, the eigenvalues (the diagonals) of are (non-negative) and thus we can build by taking the square root of each diagonal entry. To make them be upper triangular, we take the QR-decomposition ( has linearly independent columns) with such that and upper triangular. We then have . Taking we get .

9.3 Singular Value Decomposition (SVD)

We generalise the diagonalisation to non-symmetric and non-square matrices.

9.3.1 SVD

Let . There exist orthogonal matrices and such that where is a diagonal matrix (in the sense that when and the diagonal values are non-negative and ordered in descending order). and ( are orthogonal). The columns of are called the left-singular vectors of and are orthonormal. The columns of are called the right-singular vectors of and are orthonormal. The diagonal elements of , are called the singular values of and are ordered as .

Compact Form: If has rank we can write the SVD in a more compact form: . Where contains the first left singular vectors, the first right singular vectors and is a diagonal matrix with the first singular values.

Example: Let be a matrix with rank 3. Then the compact SVD of would have the form:

where is , is , and is .

SVD in terms of the Spectral Theorem

Let and its SVD.

-Viewpoint: The

- left singular vectors of , the columns of are the eigenvectors of

- singular values of are the square-root of the eigenvalues of . Note that is diagonal. If , has singular values and has eigenvalues (which is larger than ), but the “missing” singular values are ⇒ if , then the last diagonal entries of are zero.

-Viewpoint: The

- right singular vectors of , the columns of are the eigenvectors of

- singular values of are the square-root of the eigenvalues of . Note that is diagonal. If , has singular values and has eigenvalues (which is larger than ), but the “missing” singular values are ⇒ if , then the last diagonal entries of are zero.

Note that and are symmetric (thus full diagonalisation).

Singular values to Eigenvalues

The singular values are the square-root of the eigenvalues of (or use ).

Note that it’s not the eigenvalues of .

This can be seen easily as is symmetric thus which implies that and thus .

9.3.3 Every linear transformation is diagonal when viewed in the basis of the singular vectors

Every matrix has an SVD decomposition. In other words: Every linear transformation is diagonal when viewed in the bases of the singular vectors.

Proof TODO

9.3.4 Get from Singular Decomposition

Let be a matrix with rank . Let be the non-zero singular values of , the corresponding left singular vectors and the corresponding right singular vectors. Then

This follows directly from the compact SVD:

Expanding the matrix multiplication, we get:

Each term is a rank-1 matrix because it is the outer product of two vectors, and , scaled by the singular value .

Applications of SVD

invertible

If is invertible and has an SVD then it’s inverse can be easily computed using SVD as .

As is invertible, all singular values are non-zero and thus can be easily inverted (square diagonal matrix).

Pseudoinverse

The SVD provides a way to define the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse, denoted by . If , then:

where is obtained from by taking the reciprocal () of each non-zero singular value, leaving the zeros in place, and transposing the matrix.

Example Check: Condition 1: For each diagonal entry:

- If :

- If : So , giving us

Example: If , then .

If , then .

Example 2: simple matrix: Already in “SVD form” with , , and The pseudoinverse is: Notice:

- Shape flipped: is , so is

- Nonzero values inverted: ,

- Zeros stay zero

Verify: The pseudoinverse acts like an inverse in the “active” subspace (where singular values are nonzero) and projects to zero in the null space!

Notes / Tricks

An invertible Matrix does not guarantee that it’s diagonalisable

Look at which is invertible but not diagonalisable since the EW has algebraic multiplicity 2 but geometric multiplicity 1.

Nor does a diagonalisable / diagonalised matrix have to be invertible, it can have eigenvalues!